The Bayeux Tapestry > Stitched some 950 years ago, the world’s most celebrated tapestry is not a tapestry at all, but an embroidery measuring approximately 224 feet long with 58 chronological scenes; and was probably commissioned for propaganda purposes.

Diplomacy and Propaganda: The Enduring Power of the Bayeux Tapestry

BY SUSAN JAQUES

In a master stroke of cultural diplomacy, French President Emmanuel Macron announced in January 2018 that his country would loan the storied “La Tapisserie de Bayeux (The Bayeux Tapestry)” to Britain in 2022. In exchange, it’s been suggested that the British Museum lend the equally famous Rosetta Stone, taken by Napoleon’s troops from Egypt and turned over to Britain in 1801.

Though Macron’s headline-making offer represents the first time the Bayeux Tapestry would leave France in more than nine centuries, it isn’t the first time the famous work has been unfurled for propaganda purposes. In 1804, Napoleon displayed it in Paris to drum up support for his own planned invasion of England. And after occupying France in 1940, Adolf Hitler exploited it to advance his Aryan agenda.

ENIGMATIC ORIGINS

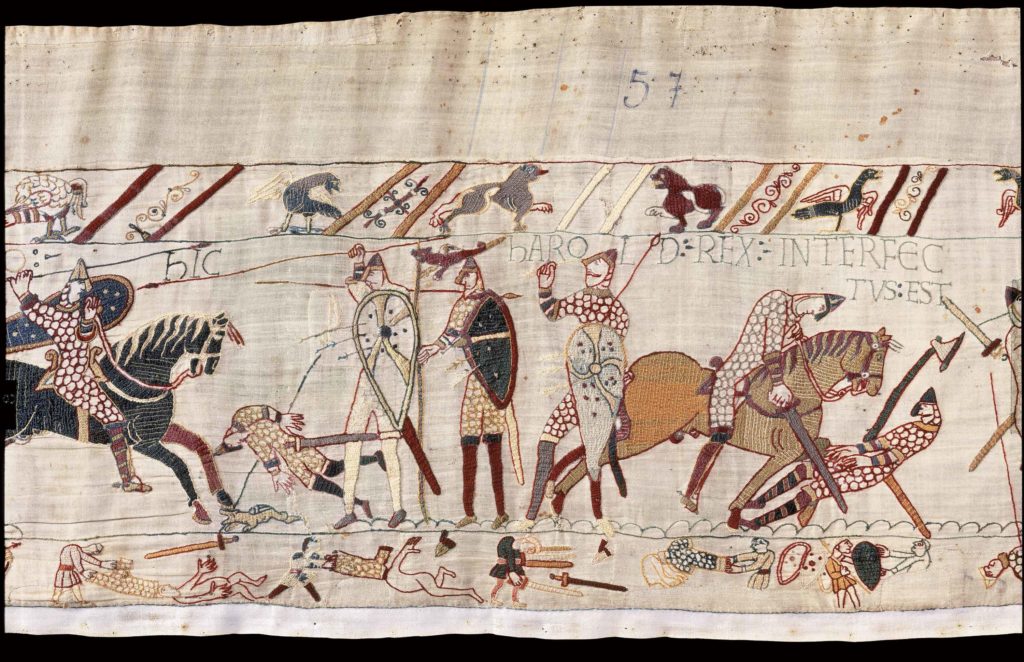

The world’s most celebrated tapestry is not a tapestry at all, but an embroidery. It was stitched some 950 years ago to chronicle and glorify the Norman Conquest of England. In 1066, William the Conqueror, Duke of Normandy, crossed the English Channel and defeated King Harold at the Battle of Hastings in southern England. After 600 years of Anglo-Saxon rule, William became England’s first Norman king. Laws, society, and architecture were transformed. French became the language of the court; Norman nobility became the new English aristocracy.

The Bayeux Tapestry was commissioned and produced in the years following the invasion, probably for propaganda purposes. Yet the name of its patron remains a matter of debate. One leading candidate is William the Conqueror’s half-brother, Bishop Odo of Bayeux, who enjoys a major role in the narrative the embroidery depicts. Other candidates include William or his wife, Queen Matilda; Queen Edith, wife of Edward the Confessor (Harold’s predecessor); and the monks of St. Augustine’s Abbey in Canterbury, where the design style of the tapestry developed.

Most experts agree that it was produced in Norman England, probably by Anglo-Saxon women, who were renowned for their embroidering skills. Its nine linen panels were hand-stitched before being joined, which points to a professional workshop, according to Alexandra Lester-Makin, a specialist in early medieval embroidery. Measuring approximately 224 feet long and nearly 20 inches high, the tapestry is composed of a central panel flanked by an upper and lower border, each measuring 2 3/4 inches high. Decorating the borders are birds, lions, dogs, and deer along with imaginary creatures like dragons, griffins, and centaurs.

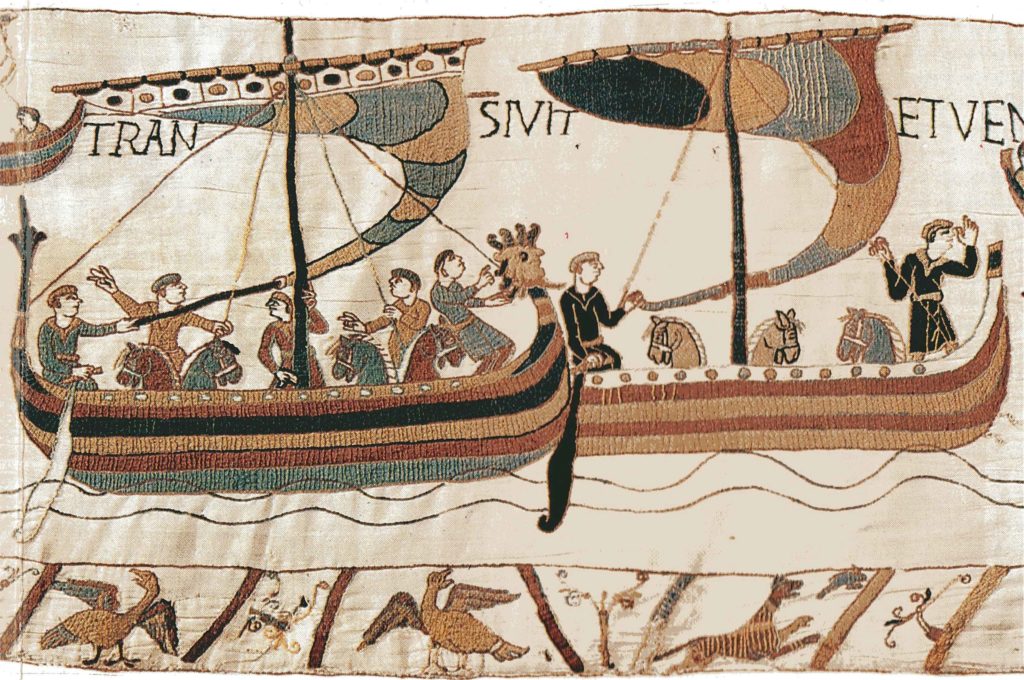

The 58 scenes unfold chronologically — starting with Harold Godwinson’s conversation with his brother-in-law King Edward the Confessor, followed by his voyage to Normandy and oath to Duke William on the sacred relics of Bayeux to uphold William’s claim to the English throne. After learning of Harold’s accession as king, William is so furious that he builds a fleet of ships and leads the Norman army across the Channel. The decisive battle at Hastings is stitched in 10 gory scenes, featuring corpses, dead horses, and the newly crowned Harold taking an arrow to the eye. Survivors are shown fleeing the hilltop battlefield.

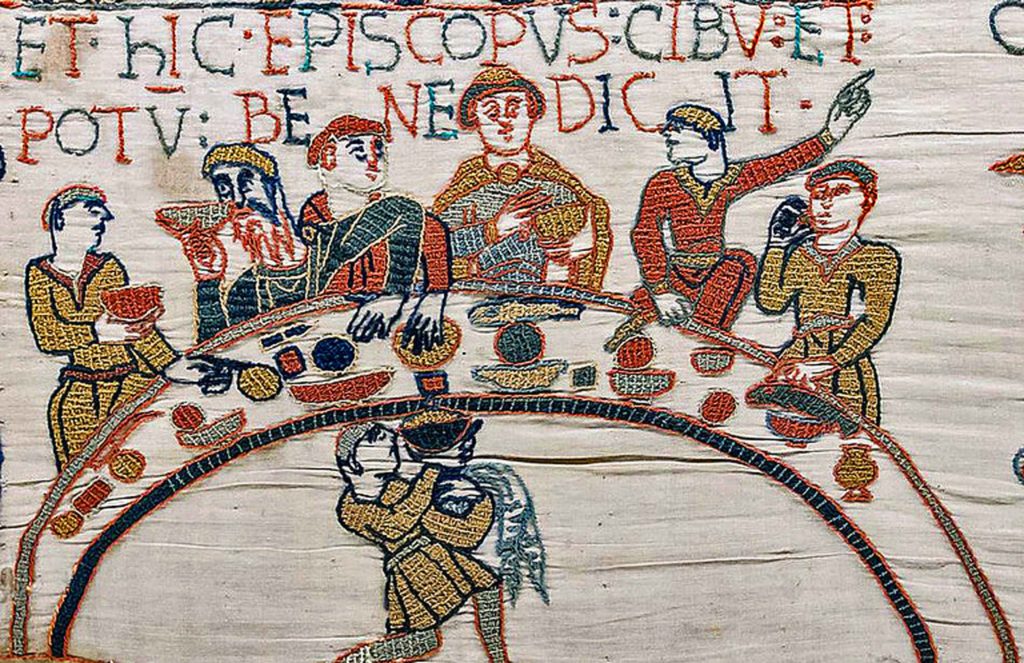

In addition to its invaluable record as a historical document, the Bayeux Tapestry offers insights into 11th-century ships, weaponry, and everyday life. Populating it are more than 200 embroidered horses and mules, 35 dogs, and some 600 humans, including three women and three children. Of these, only 15 people are identified with their names in Latin. Lumberjacks and carpenters build ships; farmers plow and sow with mules and horses. In contrast to the mustachioed, long-haired Englishmen, the Normans are clean-shaven with short hairstyles. Before the battle, the Norman soldiers are shown enjoying a hearty meal of soup, bread, and roasted chicken.

Thick wool threads against a smooth cream linen background give the epic tale a three-dimensional quality. The embroiderers worked with a limited palette of ten dyed colors of thread, all varieties of red, blue, yellow, and green, writes Gale R. Owen-Crocker in Making Sense of the Bayeux Tapestry. Rather than deluxe silk and gold thread, yellow and pale blue were used to represent gold and silver. To create the intricate scenes, embroiderers used four different stitches: the stem stitch for the 500-plus Latin inscriptions (mostly in dark blue yarn), split stitch and chain stitch for various objects, and couching stitch to fill in surfaces.

After a falling-out over his half-brother’s ambition to declare himself pope, William exiled Odo in 1082. It is thought that the tapestry was finished by this time, displayed in churches and castles throughout England and Normandy. (It is worth remembering that many viewers would have been illiterate, so visualizing this recent historical event in clearly defined episodes was essential.) The first record of the textile appears in the 1476 inventory of Bayeux Cathedral in northern France as “a very long and narrow hanging of linen, embroidered with figures and inscriptions representing the Norman conquest of England, and which is hung around the nave of the church on the Feast of Relics” (July 1–8). Confiscated dur-ing the French Revolution, the tapestry was covering a military wagon when a local lawyer rescued it and sent it to city administrators for safekeeping.

USEFUL TO MANY MASTERS

In 1803, Napoleon borrowed the textile from Bayeux for a two-month exhibition at the Louvre, which had been renamed the Musée Napoleon. To make room for the masterpiece, museum director Dominique-Vivant Denon removed several hundred Old Master drawings from the Apollo Gallery. When Napoleon attended the show’s opening, he was reportedly so taken with the parallel between a recent comet sighting and the depiction of the 1066 Halley’s Comet that appears in the tapestry that a description about it was added to the exhibition guide. Excerpts of the guide were reprinted in the influential Paris newspaper Le Moniteur.

While the Louvre showing captured the imagination of the French public, it triggered a backlash in England. A letter published in The Gentleman’s Magazine stated that England would survive “in spite of the vain, inglorious tauntings of the ambitiously mad Corsican tyrant, with all his host of myrmidons at his heels.” As Shirley Ann Brown writes in “The Bayeux Tapestry: New Approaches,” the tapestry became “a weapon in the ongoing propaganda battles between the French and the English which continued almost to the end of the nineteenth century.”

After the tapestry’s display in Paris, Denon wrote the sub-prefect of the borough of Bayeux that Napoleon was entrusting the work to the care of the locals. “He has applauded the care that the habitants of the city of Bayeux have brought for seven centuries and a half to its conservation. He has charged me to testify to them all his satisfaction and to entrust them with the deposit. Invite them to bring new care to the conservation of this fragile monument, which retraces one of the most memorable actions of the French Nation.”

In August 1805, Napoleon traveled to the port of Boulogne, poised to lead some 200,000 soldiers across the Channel for an assault on England. He told his wife, Joséphine: “I will take you to London. I intend the wife of the modern Caesar to be crowned in Westminster.”

But his dream of following in William the Conqueror’s footsteps was dashed. Britain had strengthened its coastal defenses. The superiority of the Royal Navy, recently confirmed by its destruction of the French fleet at Alexandria, led Napoleon to cancel the invasion and redirect his army toward continental Europe.

A decade after the tapestry’s return to Bayeux, an English traveler observed that it was kept “coiled round a machine, like that which lets down the buckets to a well.” In 1842, the tapestry was moved to Bayeux’s library, installed in a glass case in a new exhibition space where it remained for some seven decades. In 1870, when German troops invaded France during the Franco-Prussian war, the tapestry was removed for safekeeping.

After the war, the British government received permission to photograph the tapestry. As Carola Hicks describes in “The Bayeux Tapestry: The Life Story of a Masterpiece,” it took 180 glass negative plates to record the entire work in 1872. The Arundel Society issued the photographs in various formats. One of the full-size hand-colored reproductions was displayed at the South Kensington Museum, today’s Victoria and Albert.

In thanks, a full-size set and a half-size colored roll were sent to Bayeux. In 1931, organizers of a French art show in London asked to borrow the tapestry, but the request was denied due to concerns about the loan’s impact on tourism in Bayeux and the effect of travel on the embroidery itself.

During World War II, the tapestry was rolled on a winder inside a zinc-lined wooden crate and stored in a concrete shelter beneath Bayeux’s Hôtel du Doyen. During the German occupation of France, the SS seized on the tapestry as evidence of an early Germanic conquest of England by descendants of Norsemen or Vikings. In Nazi hands, the tapestry was used to advance German pan-nationalism and Aryan propaganda.

After its display and study, it was moved to the Abbey of Saint-Martin at Mondaye and then the Château at Sourches in 1943. In Berlin, the German archeologist Herbert Jankuhn spoke about the textile to SS chief Heinrich Himmler, who wanted to display it at his castle. In advance of the allied invasion in June 1944, the tapestry was moved to Paris, where it was stored with other looted art in the cellars of the Louvre.

After its display at the Louvre in late 1944, the tapestry was returned in March 1945 to Bayeux, which was among the first French towns to be liberated. In 1948, the textile moved to its new home at the Hôtel du Doyen. Post-war requests from London to borrow the tapestry were rejected, including one in 1953 for the coronation of Elizabeth II, a descendant of William the Conqueror. Another request in 1966 to mark the 900th anniversary of the Battle of Hastings was also denied.

A FRAGILE ARTIFACT

Over its nearly 1,000-year history, the Bayeux Tapestry has endured light, dust, temperature changes, insects, and mold. Sometime after 1860, it underwent a major restoration. Areas of missing embroidery were re-stitched with wool threads dyed with chemicals, brighter than the original threads. During this period, a new lining was attached after an early backing was lost during restoration work. According to Pierre Bouet and François Neveux, authors of “The Bayeux Tapestry,” the cloth was mended in 120 places; 518 fragments were added to patch it up.

Today the embroidery is treated much more carefully. Since 1983, its home has been a branch of the Bayeux Museum located in a former 17th-century seminary. Installed in a case at eye level behind bulletproof glass, the textile stretches out in a long straight line until the episode when William decides to construct a fleet; there it curves along a rounded corner and circles back down the other side of the hall. To preserve the linen fibers and wool threads, it is kept in a darkened space at a temperature of 18–20 degrees Celsius, with a humidity level of approximately 50 percent. In 2007, the Bayeux Tapestry was added to UNESCO’s Memory of the World register, joining the Gutenberg Bible and other unique treasures.

Today the embroidery is a hugely popular tourist attraction, with some 400,000 people visiting it each year. In 2020, an architectural competition will invite proposals for a redesign of the display aimed at improving the tapestry’s conservation environment and visual presentation. According to spokesperson Fanny Garbe, this refreshed installation will be located in the same place but with a new facility added to welcome and serve visitors. “We want to make the visit more comfortable and also enrich our explanations of the Bayeux Tapestry, William the Conqueror, etc.,” says Garbe. “In a word, to turn this museum into the public’s gateway to Medieval Normandy.”

A committee of curators and historians is slated to begin a scientific study on how to stabilize, safely transport, and display the fragile textile in Britain. Though the timing, length, and venue for the much-anticipated exhibition have not been confirmed, the British Museum is the frontrunner thanks to its capacity for large numbers of visitors, gallery space, and historical focus. Other contenders include the museum at Battle Abbey in East Sussex (site of the Battle of Hastings), along with the Victoria and Albert Museum, which regularly displays textiles.

As the UK continues to debate its departure from the European Union, this highly symbolic gesture of cultural diplomacy between Britain and France seems more compelling than ever.

SUSAN JAQUES is the author of The Caesar of Paris: Napoleon Bonaparte, Rome, and the Artistic Obsession that Shaped an Empire (December 2018, Pegasus Books). This article was originally published in Fine Art Connoisseur magazine, January/February 2019.

> Visit EricRhoads.com to learn about more opportunities for artists and art collectors, including retreats, international art trips, art conventions, and more.

> Sign up to receive Fine Art Today, our free weekly e-newsletter

> Subscribe to Fine Art Connoisseur magazine, so you never miss an issue