Marlborough College Chapel Architecture and History

Introduction 07 The first Chapel 08 George Bell’s Marlborough and the new Chapel 28 A new age 58 The role of the Chapel in College life today 71 A history of the Chapel of St Michael and All Angels, Marlborough College

4

The Master’s Preface

A walk around Marlborough College reveals an extraordinary array of architecture, the most impressive edifices being the great Neolithic Mound and the neighbouring Gothic Revival Chapel, structures which reflect the importance of the spiritual life associated with this place. The former still presents great mysteries, but the latter reflects a clear vision of the College’s foundation to send good young people out into the world.

One hundred and fifty years ago, Frederic William Farrar, Master of Marlborough, embarked upon an extraordinary refurbishment of the College’s original chapel. He was convinced that great art could enrich and elevate the minds of the young and his vision and determination resulted in exceptional work. His successor, George Bell, together with the tireless Bursar Thomas, incorporated Farrar’s works in a grand new building. The generosity shown by so many and the artistry of its makers resulted in a building which is one of the glories of nineteenth century ecclesiastical architecture. Much has changed since the time of Farrar and Bell, but the building still helps to teach lessons which are of vital importance in the community of a full boarding school. The Chapel can be a daily reminder of higher matters, and it frames the beauty of words and music in services. The building’s history and the wide-ranging generosity it speaks of are worth remembering in the rush and complexity of modern life.

I am delighted that this inspirational building – its history, architecture, art and vision – is being celebrated in two new College publications and I am enormously grateful to all those who have contributed.

Louise Moelwyn-Hughes Master

05 Marlborough College Chapel: Architecture and History

Introduction

In my teenage years I was very lucky to encounter an inspirational teacher called Jack Thomas. In his study there was a print of his old school’s Chapel, and I asked him if the building really was as fine as the picture suggested. He confirmed that it was. His great grandfather and his grandfather had been key figures in its creation, and I came to learn that Frederic William Farrar, the Master of Marlborough between 1870 and 1876 and ‘Bursar Thomas’ were both towering Victorian figures.

My interest in school buildings grew and as a postgraduate I undertook research on collaborations between educationalists and architects. When I visited Marlborough to inspect the buildings and the archives forty years ago, I was amazed by what I saw and read.

In 1985 I was fortunate to be given a job at the College and in 1986, in haste, I wrote a history to celebrate the Chapel building’s centenary. It has been a joy to revisit the subject. There is still so much to discover about this great building and its role in Marlborough College’s history, and I hope that in the future others will continue to investigate the many messages which the Chapel conveys.

Marlborough College Chapel: Architecture and History 07

Dr Niall Hamilton CR 1985-

The first Chapel

Thomas Arnold, Headmaster of Rugby, undertook his reforming work there between 1828 and 1842 but other schools took a while to follow his example. The wellestablished old schools which were investigated by the Clarendon Commission in 1861 varied greatly in size and condition, and many of the country’s old grammar schools were moribund. However, the demand for good secondary education increased as the ranks of the middle classes grew. Arnold and his followers showed boarding schools were able to promote the ‘godliness and good learning’ which the founding statutes of many schools had underlined, and between the 1840s and 1860s a radical transformation occurred which included the establishment of many new schools which soon took on the appearance of being venerable seats of learning.

At Rugby, Arnold placed great emphasis on the importance of scholarship, but he was convinced education was worth nothing unless the principles of the Christian faith underpinned it. He attempted to make the life of the school revolve around the Chapel, and he undoubtedly made a great impression on some of his boys such as the three future deans, Stanley, Lake and Vaughan, the poet Clough and the writer and Christian Socialist, Thomas Hughes. At Winchester, too, the religious life of the school was revived during George Moberly’s headmastership (1833-1860), though he was determined to avoid any

artificially induced piety and he placed less pressure on his boys than Arnold. Regardless of the successes of Arnold and Moberly, few schools rushed to build chapels in the first half of the nineteenth century. Financial conditions often prevented the construction of private places of worship, and many were reluctant to abandon ties with local parish churches. Vicars did not like the idea of losing hold of large communities within their parishes, and many associated private chapels with Roman Catholicism and feared there would be unfortunate consequences if the young were subjected to services within such places.

Marlborough College, which had been founded in 1843 for the sons of the poorer professional classes and the clergy, was intended to be the Church of England school for the South of England and it was one of the first Anglican schools to build a chapel of any architectural distinction. The College grew very quickly in its early years and the governing body soon agreed a private chapel was necessary, but it required an Act of Parliament to permit this. Services in the College’s first five years were held in St Peter’s parish church twice daily, but there was insufficient room for the boys and concealed within box pews it was easy for them to misbehave without fear of retribution. Yet here, the hard-pressed first Master, Matthew Wilkinson, delivered sermons which did make an impression on some of the young. In 1846 an appreciative twelve-year old wrote home:

Mr Wilkinson preached a beautiful sermon yesterday ... I always like Mr Wilkinson’s sermons very much, they seem so exactly suited to public schoolboys. I always fancy, too, they are so like what I have heard of Dr Arnold’s.

In 1846 a chapel was designed by the architect Edward Blore, who also produced plans for two boarding houses (A and B House), the first dining hall and the Master’s Lodge. He was a talented draughtsman, a Fellow of the Royal Society and he helped to found the Royal Archaeological Institute.

Marlborough College Chapel: Architecture and History 08

When Marlborough College opened in 1843 the concept of the English public school did not exist.

Blore, inaccurately described by many Old Marlburians as a prison architect, knew Ruskin and Sir Walter Scott. He restored Westminster Abbey and Lambeth Palace, and he worked for the Crown at Windsor, Buckingham Palace and Hampton Court.

The Vorontsov Palace at Alupka in Crimea and his Government House in Sydney are amongst his most impressive buildings. The Chapel at Marlborough, dedicated to St Michael and All Angels, cost slightly less than £7,000, a sum

which proved difficult to raise since the school’s resources were strained by fluctuating numbers.

Unlike Blore’s other work at Marlborough, the Chapel was built in a form of Gothic, a style which was being revived in the wake of the architect Augustus Pugin’s work. The austere sarsen stone edifice for five hundred boys was too wide for its length and its details were clumsy. In 1849 the Ecclesiologist, an influential but frequently scathing journal devoted to the study of

Gothic architecture, was unsparing in its criticism of both Blore and the Chapel, declaring that ‘an artist would have made it what Blore, into whose unhappy hands the building has fallen, has not the feeling to achieve.’ In contrast, the governing body was praised for having built a chapel, and it declared ‘that nothing can exceed our respect for the spirit and energy ... of this institution. They have been liberal to an excess of expenditure; their only wish has been to make the institution perfect.’

St Peter’s Church (with B House and C House in background)

09

Blore had promised he would build the College a ‘sort of cathedral’, but the Ecclesiologist believed the Chapel had ‘just that amount of sham unreality that no artist who revered his profession or his immediate work, would have been guilty of.’ Since the Chapel was detached from the rest of the school it ‘failed in that lesson which other college chapels ought to convey, that religion is part and parcel, not an isolated element of the work carried on within it’. Many of the interior furnishings were criticised: the altar, which was fitted into a ‘strange recess compounded of a fireplace and an Easter sepulchre’, was likened to a domestic sideboard.

10

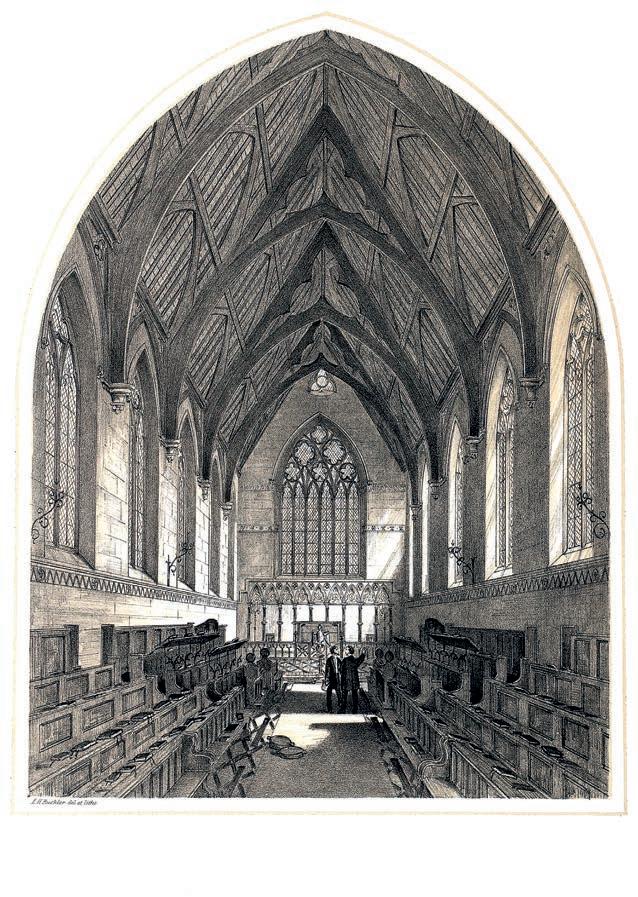

The interior of Blore’s Chapel View of the College from the west showing the Chapel, A House and the Marlborough Mound

The Chapel services received more favourable comments:

Marlborough College has, as it ought to have, a privilege which its elder sisters on the Thames and the Itchin have relinquished. Twice every day is the whole school assembled at morning and evening Prayers of the church. The punctual attendance of all the masters, the voluntary presence of so many of the household officers and the reverent behaviour of the boys, make this a sight which few who witnessed it can forget, and of the unspeakable advantage of this rule to the school it is impossible to magnify.

In 1848 the consecration service was conducted in the presence of the Bishop of Salisbury, sixty clergy of the diocese and the ordained members of staff. The choir which was formed when the building was completed was one of the earliest school chapel choirs to be formed in the country, and The Ecclesiologist noted the promise of ‘the boys and officials’ who performed on Sundays

and holidays. This body was praised by Edward Lockwood in his account of the religious services in the early days of the College:

We were all driven, much against our will, fifteen times a week to Chapel, where the services were rendered far less irksome than they would otherwise have been, by the singing: for sufficient voices were found among the host at the school to form a choir, which, had I not known the boys, and watched their distorted faces whilst they sang, I might have imagined came down direct from heaven.

These frequent choral services may have helped to convince some people that the accusations of Tractarianism which were made against Wilkinson were correct. The Record , an Evangelical journal, recommended that clergymen of true Protestant convictions could not send their offspring to Marlborough, and it implied they should send them to Rossall

in Lancashire, founded in 1844 as the Church of England School for the north of England.

In an attempt to alleviate fears about the nature of the school’s religion, Wilkinson followed Arnold’s example and published a volume of his sermons, but this did not reverse the school’s fortunes.

Marlborough’s early years were fraught with difficulties. The famous rebellion by the pupils occurred in 1851 and the unfortunate Wilkinson left the College for a quieter existence as Vicar of West Lavington. His successor at Marlborough was George Cotton, who had been a Housemaster at Rugby and almost certainly the model for the popular young master admired by Rugbeians in Thomas Hughes’s novel Tom Brown’s Schooldays (1857).

11

Marlborough College Chapel: Architecture and History

Cotton introduced an innovative curriculum with a broader range of subjects to suit more boys and he regained control of the large, disorganised and turbulent community by reforming the prefect system and introducing organised games, run by Old Rugbeians who had just left university. They were cheap to employ as teachers and very effective. Cotton’s sermons in the Chapel rationalised his method of keeping order. He did not want games to be thought of as just a way occupying boys outside the classroom and as a means for keeping them out of trouble, so he used the Sunday services to promote the Graeco-Renaissance idea of the ‘complete man’, and to this concept he added a strong Christian emphasis. He stressed that the motive for success on the games field should be godliness.

All our powers and faculties, the limbs which are strong and healthy, the understanding which is strengthened and developed by our daily Studies, are equally the workmanship of Him who has also reunited us to Himself in Jesus Christ. And, therefore, in gaining wisdom and knowledge and bodily strength, we are carrying out his gracious purposes no less surely, though more indirectly than when we are reading the Bible or kneeling before Him in prayer.

Cotton was the first headmaster to promote athleticism from the pulpit. In doing so he helped to justify and encourage the virtually uncontrollable enthusiasm for sport which was channelled by later schoolmasters into a fierce competitive spirit and tribal loyalties to the house and the school. He was aware of the dangers of organised games though, and he explained to Marlburians that it was harmful to concentrate on sport at the expense of academic endeavour: ‘by a strange perversity’, he declared, ‘we employ God’s gift for our own

injury’. He believed that both intellectual and bodily excellence were only really blessed when they reflected moral and religious goodness; when they taught unselfishness, right principles, and justice. Ironically, Cotton’s work redirected the reform of the public schools onto a path which would have displeased Arnold. Whereas the latter had attached enormous importance to academic achievement and chose his prefects from the ranks of the best scholars, headmasters from Cotton’s time onwards chose theirs from the sports fields. ‘Muscular Christian’ games-playing staff came to be thought of as essential for a good Victorian boarding school, and in the latter half of the nineteenth century the concept that outward physical excellence denoted moral goodness became increasingly popular.

Cotton was, nevertheless, essentially a teacher in the Arnoldian mould. His original letter of inquiry about the headmastership of Marlborough, which was written before the college opened, posed questions which reflect his Rugby training:

Will the Headmaster have the appointment of other assistant masters, beside the second master?

Will the whole internal disciplinary arrangement of the school be under his authority?

Is it intended that the headmaster should preach and perform Divine service for the boys?

Will there be a school chapel?

12

Marlborough College Chapel: Architecture and History

George Cotton, Master of Marlborough 1852-58

Like Arnold, Cotton became the school’s principal pastor, but whereas Arnold made a point of using the Chapel on Sundays and saints’ days only, Cotton declared he was ‘decidedly in favour of the daily chapel plan’ which had been established by Wilkinson.

Cotton’s talents as a preacher helped him to become Bishop of Calcutta, though his sermons, like Arnold’s, must have been hard for boys to understand. They are laden with Old Testament scholarship, and they make vague references to diabolical sins. However, his published sermon about school friendships is particularly interesting because it reveals a remarkable tolerance of friendships between senior and junior boys. Cotton glorified intense school relationships in terms which would have shocked schoolmasters in the latter decades of the nineteenth century as being naïve. Cotton, however, liked to place implicit trust in his boys:

We trust you, we believe the word of every boy till by his general character, his ambiguous and shuffling answers, or his actual detection in falsehood of subterfuge, he forces us to withdraw our confidence.

Such complete trust was not a characteristic of the late Victorian public school. As these institutions grew in size and complexity, they became less intimate and relationships between boys and masters became more formal.

The magnificent eagle lectern in the Chapel might have been commissioned in Cotton’s time. It was in the Chapel by c.1862 and possibly pre-dates Cotton. This fine work is a relatively early example of the revival of the medieval-styled brass lectern which came in the wake of the Gothic Revival. Interest had been aroused by the discovery of Pre-Reformation lecterns such as

13

Marlborough College Chapel: Architecture and History

the one at Oundle, which had been fished out of the River Nene in the early years of the century. One was found in the marshes at Isleham in Cambridgeshire, another in the churchyard of Snettisham in Norfolk, and perhaps the most remarkable discovery was Norwich Cathedral’s pelican lectern, retrieved from the garden of the Bishop’s Palace and returned to the Cathedral in 1841. In the same year, Pugin’s magnificent interior of the Roman Catholic Cathedral of St Chad in Birmingham was furnished with a splendid eagle lectern. Marlborough’s lectern could well have raised a few eyebrows as being a suspiciously ‘popish’ object in an Anglican foundation. It would certainly have stood out in an otherwise austere interior.

Cotton, who was thought to be destined for great things after his career in India, died tragically on the 6th of October in 1866 when he disappeared while boarding a boat on the Gorai river, having just consecrated a cemetery at Kushtiâ. It is believed he fell into the river and was carried away by a strong undercurrent, but stories about this event vary and the exact circumstances of his death remain unclear. His name lives on in India because of the schools he founded, and today there is a well-known phrase which is associated with him. As part of his philanthropy, he ordered hundreds of pairs of socks to be sent for the children to help against the cold, blessing all the socks on arrival. According to one story, a zealous member of staff one day distributed socks before the blessing, so thereafter every time a shipment arrived a note was placed on them to the effect: ‘Cotton’s socks for blessing’. Cotton’s socks soon became corrupted to cotton socks. Another account relates how Cotton asked for donations of clothing, often emphasising ‘warm socks’ for the children, and ladies all over England spent their time knitting socks for him. When Cotton died,

a despatch was sent to the Archbishop of Canterbury to ask: ‘Who will bless his cotton socks?’

The third Master of Marlborough, George Bradley (1858−71), had been one of Arnold’s pupils (the model for ‘Tadpole’ in Tom Brown’s Schooldays) and an assistant master at Rugby between 1846 and 1858, a job which was both more secure and lucrative than the post he acquired at Marlborough. Bradley was chosen by Cotton rather than the Council and he carried on the work of securing the school’s existence: by the time he left the school was free of debt and boasted an outstanding academic tradition. Bradley was one of the greatest teachers of classics and divinity in the nineteenth century. It is interesting to note that Tennyson sent his son Hallam ‘not to Marlborough but to Bradley’. In 1871 Bradley left the college to become Master of University College Oxford; in 1874 he was appointed Chaplain to the Queen and in 1882 he was made Dean of Westminster, a post which he held for twenty-two

years. Although Bradley left Marlborough in 1871, he was to contribute to the story of the Chapel fifteen years after his departure, and he served on the College’s Council for the rest of his life. Bradley’s wife, Marian, also made a great contribution to the life of the College and in the vaulted antechapel there is a memorial to her which states that that at Marlborough she spent ‘twelve useful and happy years, loving and beloved’. In the vestibule to the north of the antechapel there is a fine memorial to Charles Musgrave Bull, who married into Bradley’s family. He was a Fellow of University College Oxford, who taught at the College between 1854 and 1893 and who became a member of Council in 1895. It was made by the distinguished Old Marlburian sculptor Edwin Roscoe Mullins, best known perhaps for his work at the Harris Museum in Preston, where he made the monumental figure group for the building’s pediment, depicting Pericles, Sophocles, Socrates and other figures from the Hellenistic era.

Marlborough College Chapel: Architecture and History 14

The memorial to C M Bull

Before Frederic Farrar began his five-year headmastership of Marlborough in 1871, he had achieved fame through his writing. Farrar had been an assistant master under Cotton between 1852 and 1855 and it was to Cotton that he dedicated his well-known work Eric, or Little by Little (1858), and it is this rather than Thomas Hughes’s Tom School Brown’s Schooldays (1857) which is the real literary reflection of Arnoldism. Eric, with its tale of the corruption of a young boy by evil companions, is more akin to the concerns expressed by Arnold than the robust heroes of the novel about Rugby. The story dwells on the dangers of childish transgressions and emphasises the importance of

the battle which should be fought against the temptation of sin. Farrar continued to write at Marlborough and his eminence increased, particularly after 1874 when The Life of Christ and other Theological Writings was published, a book illustrated with works by contemporary artists such as Gustave Doré and Holman Hunt. He exerted a wide-ranging influence upon the country in the final decades of the nineteenth century. Like Bradley he became Chaplain to Queen Victoria and he went on to Westminster to become Vicar of St Margaret’s and a canon of the Abbey, where he worked closely with Bradley. In 1883 he was appointed Archdeacon there and in 1895 he became Dean of Canterbury.

Farrar’s sermons were filled with history, poetry, and biography, and he mentioned the work of Cotton frequently in his addresses. At Marlborough he tried to harness the passion for organised games by underlining the fact that boys went to school to improve their minds rather than their sporting prowess:

Do not think I disparage the physical vigour at which I daily look with interest, but it is impossible to repress a sigh when one thinks that the same vigour infused also into intellectual studies, which are far higher and nobler, would carry all success and prosperity in life irresistibly before you.

Like Cotton he made cloudy references to terrible sins, and he reminded those young with ‘insolent, guilty and polluted souls’ of the watchfulness he expected of the prefects in the classrooms and the dormitories.

Farrar was far from being a typical Victorian headmaster though. He made Marlborough a pioneering school in the teaching of science and later, as Archdeacon of Westminster, he preached at Darwin’s funeral. He was also an aesthete and a collector of modern pictures. He knew Ruskin, G.F. Watts and Burne-Jones and he visited European galleries where he developed a deep interest in the Renaissance. Unlike Thomas Arnold, who had no great interest in art, Farrar believed it was ‘a consummate teacher of mankind ... I look on all true and worthy Art as a thing essentially sacred’. When he was at Harrow, he decorated his classroom with antique casts and ‘Fra Angelico’s blue Madonnas and rose-coloured angels on golden backgrounds as models of colour’. He fought to make boys appreciate art and once commanded a dull boy not to sit there ‘gorgonizing me with your stony British stare’.

Marlborough College Chapel: Architecture and History 15

Frederic William Farrar, Master of Marlborough 1871-76

16 Marlborough College Chapel: Architecture and History

The redecorated Chapel looking East

At Marlborough he was determined to improve the state of the Chapel which he remembered from Cotton’s time with its unsightly walls and ‘those unstained windows, that unadorned roof, that unmarked east end.’ Bradley had wished to enhance the building but the financial consequences of the scarlet fever epidemics of the 1860s had prevented any improvements in his time.

In February 1872 the College’s auditor, Pattison, offered some money to enhance the Chapel. Relations with the College’s distinguished architect George Edmund Street had been strained as a result of some work concerning the drains of the new boarding houses of Cotton and Littlefield. Although Street was re-employed by the College to build the Bradleian, the library dedicated to Bradley, it was decided the new work in the Chapel should be given to the equally distinguished architect George Frederick Bodley, who had a connection with Marlborough through his brother-in-law, John Fowler, who had been an assistant master at Marlborough between 1849 and 1857. A popular supporter of Cotton’s reforms, Fowler formed a friendship with Farrar which endured after their time together as

colleagues. They toured Italy in the winter of 1862, and through Fowler he would have learnt about Bodley’s wish ‘to secure the services of painters like Holman Hunt, Rossetti and other such men for the decoration of churches.’

A scheme was devised by Bodley and his partner Thomas Garner which was to be executed in two phases by the Cambridge-based firm of F.R. Leach. The decoration of the ceiling was completed in 1873 and elaborate wall paintings were finished in 1875 by Leach’s decorator David Parr, whose remarkably painted home in Cambridge still exists. Parr’s work at Marlborough did not last long and can now only be appreciated in black and white photographs. The organ was rebuilt and housed in a splendid case by Bodley, and twelve small panels of angels were commissioned for the east wall either side of the new stained glass east window by Clayton and Bell. The angels were painted by the Pre-Raphaelite artist John Roddam Spencer Stanhope, of which only eight survive, now either side of the present west window. The modelling of these figures reflected the influence of Burne-Jones, and The Marlburian commented that they were ‘angels of Fra Angelico transformed by infusions of the canons of the late Revival’.

Marlborough College Chapel: Architecture and History 17

They are not refined work but they undoubtedly enhanced the appearance of the east end of Blore’s chapel. The four angels nearest the original east window have disappeared without trace. It is hard to make out their forms clearly from old photographs, but two of these do bear a resemblance to two of the four angels painted by Spencer Stanhope for the organ-case of the church of St Martin-on-the-Hill, Scarborough in the early 1870s, the first example of Bodley and Garner and the painter working together. It is tempting to think that Spencer Stanhope re-used the designs when it came to the Marlborough work.

Spencer Stanhope was an Old Rugbeian, and he would have known both Cotton and Bradley when they taught at the school, and with the Fowler and Bodley connection he would have been an obvious choice of artist for Farrar in his schemes for the Chapel. Bodley may well have met Spencer Stanhope as early as the 1850s at the Hogarth Club in Fitzrovia, and they became good friends. He was the first owner of The Watergate, which the artist showed at the Dudley Gallery in 1870. The architect enjoyed holidays at the artist’s home in the Villa Nuti at Bellosguardo, near Florence, which

Spencer Stanhope made his permanent home after 1873 because his asthma prevented him from staying in England. Bodley and Spencer Stanhope later collaborated with work on the Anglican churches in Florence, St Mark and Holy Trinity.

Farrar’s adornment of the building included a stained-glass window by William Morris, the artist, fabric and furniture designer, poet, conservationist and social reformer who founded the Arts and Crafts Movement, and who had worked with Spencer Stanhope on the famous Oxford Union murals. Morris had been a boy at the College between 1848 and 1851, and he left in the wake of the great rebellion of that year. Bodley had been one of Morris’s earliest supporters, and the latter’s first extensive stained-glass scheme is at the architect’s church of All Saints, Selsley in Gloucestershire, built in 1862. However, by the time the Marlborough work of 1875 had been commissioned Bodley’s friendship with Morris had come to an end because he felt he could no longer control him in his decorative schemes, so this part of Farrar’s refurbishment might have caused both the architect and the artist a degree of anxiety.

18 Marlborough College Chapel: Architecture and History

The redecorated Chapel looking West

19

Marlborough College Chapel: Architecture and History

The Morris window was funded by Old Marlburians and dedicated to the scholars of the College. It is important because it was one of the first works to be produced by William Morris’s reorganised firm. Dissolving the old firm of Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co. had been complicated, but Morris felt his partners were focusing on their own interests and the collaborative energy of the firm had dissipated. Starting afresh he was in sole control but he was short of money, so the commission for the Marlborough window must have been welcome. Morris was responsible for the overall design and the making of the glass, but the figures, depicting the biblical boys Samuel and Timothy, were drawn by his friend Edward BurneJones, father of Philip Burne-Jones who had just started at the College. The figures have faded but the decorative foliage is still vibrant, and the window is notable because of the early use of the acanthus leaf motif, one of Morris’s most successful designs, which anticipated the flowing organic forms of Art Nouveau in the 1880s.

It is interesting to note that at the time Philip Burne-Jones was preparing to enter Marlborough (at the suggestion of William Morris), his father was painting one of his most famous works, The Beguiling of Merlin (1872-76), the story relating to Merlin’s entrapment by Nimue, the Lady of the Lake. Merlin was reputedly buried in the great four-thousand-year-old Neolithic Marlborough Mound to the south of the Chapel, but this belief has its origins in the twelfth century.

20

The Scholars’ Window by William Morris and Edward Burne-Jones Left: Original Cartoon Right: The window

Just before he left Marlborough, Farrar commissioned his most important works for the College in the form of twelve paintings. The series, entitled The Ministry of the Angels on Earth, was almost certainly inspired by the Chapel’s dedication to St Michael and All Angels. In 1864, while Farrar was still a master at Harrow, he had preached at Marlborough on ‘the angels of God’ and described how in times of crisis in human life angels appear as messengers. The idea for the paintings may well have been Bodley’s but it was embraced by an enthusiastic Farrar who appreciated the opportunity to bring modern paintings, inspired by the Italian Renaissance art, into the world of a Victorian public school. It was a brave gesture to have undertaken this commission, and with his move to Westminster he must have regretted not being able to witness the arrival of all the works.

The paintings, each measuring 4ft 2in by 5ft 6in, were painted in oil with gilding rather than in tempera, a medium which Spencer Stanhope had specialised in. They were made in the artist’s Florentine studio, beginning in 1875 and delivered to Wiltshire in instalments between 1875 and 1878. Bodley and Farrar may well have been aware of the extraordinary discovery in 1847 of the latefifteenth-century murals in Eton’s Chapel, and they would have appreciated the long walls of Marlborough’s Chapel would be enhanced greatly by painted imagery which could be vehicles for both religious instruction and aesthetic appreciation. Regardless of Prince Albert’s protests, Eton’s murals were covered up rapidly because, although they were recognised as being of great importance, their Pre-Reformation subject matter was considered inappropriate, and it was not until 1923 that they were revealed, when George Gilbert Scott’s concealing wooden canopies were given to Lancing to help with the furnishing of Nathaniel Woodard’s great chapel.

21

Marlborough College Chapel: Architecture and History

Many headmasters at this time worked on making the chapel the centre of school life to combat sinfulness and immorality, but as Bodley’s biographer Michael Hall has written, Marlborough ‘was unique in bringing the power of art to bear on this fraught subject.’ Farrar was one of the first educationalist to act on the belief that the minds of boys could be elevated by fine art, and his success in winning over the College’s Council in his expensive artistic enterprises was remarkable. Mention should be made of other heads of the

period who realised the benefits of fine architecture and fittings in their chapels. William Sewell, the first Warden of Radley, collected important works of art, and Edward Thring of Uppingham appreciated working with George Edmund Street. At Winchester, George Ridding collaborated with William Butterfield, the great High Victorian architect who Frederick Temple employed at Rugby. Work proceeded slowly with the great Woodard school chapels and at Wellington, Edward Benson kept a close eye on all decorative aspects of George Gilbert Scott’s chapel. The nature of Farrar’s

commission was extraordinary though, and the fact that the paintings were undertaken in Florence made his project all the more audacious. There is only one other scheme of decorative work which is comparable, undertaken between 1912 and 1923 at Christ’s Hospital’s Chapel by Frank Brangwyn, who painted sixteen tempera murals illustrating incidents in the history of the Christian Church. The celebrated architect of the chapel, Aston Webb, knew the Chapel at Marlborough having worked on the design of Field House (now Morris House), completed in 1912.

Marlborough College Chapel: Architecture and History 22

The exterior of the Chapel in Farrar’s time

In all his artistic ventures Farrar was assisted by the College’s remarkable Bursar, John Shearme Thomas, who had been one of Fowler’s pupils and who had been an exact contemporary of William Morris. Thomas, who married one of Farrar’s daughters, became a friend of Bodley. At Marlborough he gained considerable architectural knowledge by working closely with such eminent figures as William White, George Edmund Street, Arthur Blomfield, Norman Shaw and Alfred Waterhouse. Thomas, who contributed so much to the life of the College, went on to play a crucial role in the Chapel’s history in the 1880s. When he died in office in 1897, Dean Bradley declared after the funeral that since the death of Thomas Arnold, ‘no death has left such a gap in any school.’ A friend recalled that ‘a thousand Marlburians stood beside his grave in little Preshute churchyard, sorrowing that they should see his face no more.’

The importance which Farrar attached to art and the support which he received from Bursar Thomas is an extraordinary tale. The best of the Marlborough Spencer Stanhope paintings are very fine works, but the making of some of these paintings for a distant northern chapel after the departure of the sympathetic Farrar presented the

artist with considerable challenges. Farrar’s vision and the messages which the paintings were supposed to convey became blurred, and today it is easy to see why a degree of upset was caused: the androgynous appearance of some Spencer Stanhope figures and the amounts of bare flesh some of them displayed were not in tune with the school world of the 1870s and 1880s. Furthermore, the paintings would have presented a strange modernity, which may be hard to appreciate today. For all their Quattrocento roots and biblical subjects, the rich colour in these works and the eerie settings depicted were far removed from the experiences of art, past and present, of those who visited and attended services in the Chapel at this time.

Farrar’s artistic agenda at Marlborough reflected concerns with the growing emphasis on ‘manliness’ and toughness, and was a reaction to the growth of Muscular Christianity as espoused by Thomas Carlyle, Charles Kingsley and indeed sport-obsessed schools, where the rise of organised games had been fuelled by the conviction that outward beauty denoted inner goodness. Farrar wished to counter this with a spiritual and intellectual reform at Marlborough which embraced art. Madeleine Thiele has described

how Spencer Stanhope’s work was ‘part of the mid-to late Victorian movement of art, poetry and literature that sought to define and create a vision of manliness that was sensual and open and in contradistinction to the more muscular and heroic forms favoured by conservatives.’ She has observed that in in some respects the artist’s Marlborough work was the visual equivalent of some of the writing of Charles Swinburne and Walter Pater.

Writing in 1998, Franceso Fiumara commented that The Ministration of Angels on Earth has become the most neglected work of an undeservedly ignored artist. Spencer Stanhope was a man of private means, and he did not seek popularity. His life as a jovial and hospitable but socially unambitious expatriate in Florence kept him out of the public gaze, and because Marlborough Chapel is a private chapel his most ambitious work has remained relatively unknown. The tide is now turning and he is receiving more attention.

The paintings will be analysed in greater detail by Dr Simon McKeown’s work which complements this history of the chapel, but a brief account of them is necessary here.

23 Marlborough College Chapel: Architecture and History

THE OLD TESTAMENT

(North side of the nave from west to east)

The Expulsion from Eden

Ne reminiscaris

Domine delicta nostra (Remember not Lord our offences)

This scene from the Book of Genesis 3: 22-4 shows Adam and Eve, full of fear and shame, being banished from the east side of the Garden of Eden by ‘cherubim and a flaming sword flashing back and forth to guard the way to tree of life.’ This was Spencer Stanhope’s second version of The Expulsion, the original having been rejected in July 1878 because too much of Eve’s flesh was exposed. A photograph of the Chapel’s interior taken at this time shows the painting’s absence. The excuse used for the rejection was the unsatisfactory depiction of St Michael and the colour of the Garden of Eden’s wall. The draughtsmanship was criticised. The artist responded: ‘Alas for Fra Angelico! And Lippo Lippi! It was from them I cribbed the idea!’

This work, the last to be installed in the Chapel, arrived in 1879. What might be the first version of The Expulsion is now in the collection of Liverpool’s Walker Art Gallery, although the date given for this work is c1900.

Abraham Entertaining the Angels

Adjutorium nostrum in nomine Domini (Our help is in the name of the Lord)

Genesis 18:1-16 describes how Abraham and his wife Sarah had longed for children. One day three travellers appeared at their house, and Abraham invited them to eat and rest. The visitors were angels, and they announced that the elderly Sarah would have a son within a year. The seated angels are awkward, but the occasion related in this passage is uncomfortable and Sarah was frightened by what they said. Wilfred Blunt, a pupil at Marlborough in the 1920s described how the paintings were given names by the boys. They used to make fun of this work by calling it ‘Your beard is in my soup.’

The painting arrived in the spring of 1878, together with Lot Rescued from Sodom, The Three Holy Children, The Temptation of Our Lord and The Agony in the Garden of Gethsemane.

Lot Rescued from Sodom

Nos qui vivimus benedicimus Domino (We that live bless the Lord)

Genesis 19:24-25 describes how Lot, his wife and their two daughters are led by an angel out of the wicked city of Sodom – a place which filled Victorian schoolmasters with horror – prior to its destruction by God. They had been told not to look back on the terrible scene, but Lot’s wife disregarded the warning and turned into a pillar of salt. In this richly coloured work Lot’s wife is on the point of turning round to the left, and her posture contrasts with the focused rightward movement of Lot and his daughters, treading in the footsteps of the angel. Spencer Stanhope increased the scale of the figures in this, one of the last works of the series to be painted, so they would read more clearly at a distance.

Marlborough College Chapel: Architecture and History 24

Hagar in the Wilderness

Ego te potavi aqua salutis de petra

(I gave you the water of salvation from the rock)

Genesis 21:14-20 describes the tale of Hagar, an Egyptian slave to Abraham, with whom she had a son, Ishmael. Abraham’s wife became jealous and asked her husband to banish them to the desert. Sent away with only small rations of food and water, Hagar and Ishmael were saved from dying of thirst by an angel.

This painting, with its hovering angel, makes an interesting comparison with the Botticelliinfluenced Night and Sleep (1878) by Evelyn de Morgan, Spencer Stanhope’s niece and pupil. She became a successful artist and married the famous ceramicist, William de Morgan. There is now a de Morgan Museum at the Spencer Stanhope family home at Cannon Hall, Barnsley in Yorkshire.

The Sacrifice of Isaac

Semen ejus haereditabit terram (His seed will inherit the earth)

Genesis 22:1-18 describes how God tested Abraham by telling him to sacrifice his son Isaac. As Abraham began his terrible task, he was stopped by an angel. God commended Abraham’s pious obedience and a ram which appeared was slaughtered instead. This depiction of Isaac, which pushes the limits presented by the neighbouring languorous Ishmael still further, must have disturbed many and irreverent boys gave it the nickname ‘The appendix operation.’ Compositionally, it is a striking piece. In front of a sweeping Leonardesque landscape, Abraham leans over his son who is bound on an elaborately constructed pyre of wood, the knife rhyming with the body of the hovering angel, whose form again invites comparisons with Evelyn de Morgan’s work.

Hagar in the Wilderness and The Sacrifice of Isaac were the first paintings to be installed in the Chapel, arriving at Marlborough in the Christmas holidays of 1875-6.

The Three Holy Children

Si ambulavero in medio tribulationis vivificabis me (Though I walk in the midst of trouble, You will revive me)

The Book of Daniel 3:1-30 describes how King Nebuchadnezzar constructed a golden image of himself which he ordered the people to worship. Shadrach, Meschach and Abednego defied his order, refusing to worship anyone but God. Nebuchadnezzar ordered that the young men be thrown in a furnace. They were seen walking around in the fire unharmed, with a fourth figure. Praising God, they emerged from the furnace with an angel, who had made the flames feel like a cool breeze. Nebuchadnezzar then ordered the people to worship their God instead of the idol. Spencer Stanhope’s painting of this scene, with three bored-looking children, is not one of his strongest works.

25 Marlborough College Chapel: Architecture and History

THE NEW TESTAMENT

(South side of the nave from west to east)

The Annunciation

Ave Gratia plena.

Dominus Tecum

(Hail full of Grace. The Lord is with you)

Luke 1:26-38 describes how the Archangel Gabriel appeared to Mary to tell her that she would conceive and bear a son through a virgin birth and become the mother of Jesus Christ. On seeing how troubled Mary was Gabriel declared Fear not, Mary: for thou hast found favour with God . In this painting Gabriel, holding the white lily associated with the Virgin, shows great care for the kneeling Mary just as she shows such humility. The tenderness and delicacy of the two contrasts with the comet-like energy of the Holy Spirit descending in the form of a dove. The Virgin Mary is often depicted in a rose garden, and here the flowers provide a marked decorative contrast to the cypresses and the architecture in the background. The composition has a strength which can be compared to the best work by Burne-Jones.

The Gloria In Excelsis

Hodie in terra canunt angeli, laetanture Archangeli (Today on earth the angels sing, the Archangels rejoice)

Glory to God in the highest was the hymn sung by the angels announcing the birth of Christ to the shepherds in Luke 2:14. After hearing this they set out to Bethlehem to become part of the story of the Nativity. The broken fence presents a glimpse of the horizon and the dawn of a new age.

The Annunciation and The Gloria in Excelsis were the third and fourth works to arrive at Marlborough in the summer of 1876, right at the end of Farrar’s time at Marlborough.

The Temptation of Our Lord

Custodient te in omnibus viis tuis (To keep you in all your ways)

The narrative of this episode is given in the gospels of Matthew, Mark and Luke. After being baptised, Jesus was tempted by the devil after forty days and nights of fasting in the Judaean Desert. Jesus refused each temptation and returned to Galilee to begin his ministry. Spencer Stanhope depicts Christ as an unmasculine figure in a state of collapse. In Matthew 4:1-11 he is described as being tended by two angels while the frustrated devil perches on the edge of the cliff. Boys did not take to this picture and it was nicknamed ‘The Skating Accident’.

Marlborough College Chapel: Architecture and History 26

The Agony in the Garden The Sepulchre The New Jerusalem

Deus, Deus meus respice in me (God, my God, look upon me)

St Luke 22:39-46 describes how after the Last Supper Jesus went into the garden where he experienced great anguish and prayed to be delivered from his impending crucifixion while also submitting to God’s will. An angel appeared to strengthen him.

In this, one of the artist’s finest works, the foreshortened figures of the slumbering disciples are nods to the depictions of this scene by Masaccio and Giovanni Bellini, and the winding pathway and trees to the left, grouped like a crucifixion, are indebted to Bellini. The flowers around the feet of the distressed angel are portends of the Resurrection, and the verticality of the cypress trees, symbols of both mourning and eternity, point to the heavens, echoing Christ’s hands.

Nolite timere, Scio enim quod Jesum quaeritus (Do not be afraid, for I know you are looking for Jesus)

All four gospels tell the story, with variations, of how the tomb of Jesus was found empty after his crucifixion. The Three Marys come from Luke 24: 5, And as they were afraid, and bowed down their faces to the earth, they said unto them, Why seek ye the living among the dead? The presence of the angel, rather than two men at the sepulchre, is referred to in Matthew, Chapter 28, verses 2−7.

Spencer Stanhope’s depiction of the scene is composed with great mastery. The rhythmic beauty of the women’s outreaching arms is counterbalanced by the verticality of the angel and the angular architectural quality of the tomb. The austere background contrasts with the garden of flowers at the angel’s feet, emblematic of the joyful news.

Another version of this work can be found in the Art Gallery of New South Wales, and another, on a smaller scale, formed part of the Altar of the Resurrection in Holy Trinity Florence (1892-6) which was dismantled and sold off in the 1960s. Its present whereabouts is unknown.

Pleni sunt coeli et terra gloria tua (The heavens and earth are full of your glory)

Wilfred Blunt described this painting of the Revelation of John as being the boys’ favourite. It is a depiction of the Revelation of John 21:1−4, And I saw a new heaven and a new earth: for the first heaven and the first earth were passed away; and there was no more sea. And I John saw the holy city, new Jerusalem, coming down from God out of heaven, prepared as a bride adorned for her husband

This painting, vulgarly known as ‘Pie in the Sky’, shows ‘an earth-bound St John pointing at the New Jerusalem hovering Laputa-like in the empyrean.’ The painting was also referred to as ‘the Forced landing.’ It is indeed a strange work, and its eerie, unearthly qualities give it a place in the early history of nineteenth century Symbolist painting.

The Sepulchre and The New Jerusalem arrived at Marlborough together early in 1877, marking the halfway point in the arrival of the series.

27 Marlborough College Chapel: Architecture and History

George Bell’s Marlborough and the new Chapel

28

During George Bell’s time as Master between 1876 and 1903 Marlborough enjoyed prosperity. For many schools this was an era of consolidation rather than an age of progress, but in an era which witnessed many social reforms, some Heads became convinced attempts should be made to make their pupils more aware of the deprivations suffered by the less privileged, and they tried to involve them in work which might help to right social injustices. Total isolation of school communities ceased to be regarded as being desirable and many of the larger schools founded missions in poor areas of cities.

The pupils of Marlborough were moved to action by Bishop Walsham How, the Suffragan for North and East London, and in the Revd E.F. Noel Smith the Marlborough Mission in Tottenham obtained a leader of a remarkable quality. Built between 1886 and 1887 the £10,000 mission church of St Mary’s was erected to designs by J.E.K. Cutts, a large red brick church which was capable of seating 720. The College gave £3,400 towards the cost of its construction. The mission went on to build clubs and small groups of Marlburians became involved in the work at Tottenham, but direct connections with the school were limited because of the problems presented by distance and transport. Today St Mary’s is a vibrant church, and although Marlborough’s focus has shifted to more local concerns, the College is commemorated there by stained glass windows and memorials which reflect a complex tale of close relationships and commitment to Tottenham.

29 Marlborough College Chapel: Architecture and History

George Charles Bell, Master of Marlborough 1876-1903

The greatest building project in the College’s history was undertaken during Bell’s time. Although Blore’s building had been extensively refurbished between 1873 and 1875, it was felt the building required significant alterations because it was too cramped and on hot days in the summer many boys fainted during services. The chapel building had been designed to seat 500 boys and a relatively small staff, but by the 1880s there were 600 boys in the school and 30 masters. Furthermore, it was felt the architecture of the building was poor and even the recent effective (and expensive) painting of the interior walls did not compensate for its aesthetic deficiencies. At first it was decided to lengthen the building, raise the walls by ten feet and enlarge the windows, but this scheme was abandoned when a survey revealed how badly Blore’s work had been executed. On 11th May 1884 Garner wrote to Bursar Thomas, to inform him that the foundations were very bad ‘and the walls most shamefully built, far worse than could have been thought possible.’ He described how

the walls had been built on a thin layer of concrete ‘never more than 9 inches and frequently only 3 inches in thickness; whilst the concrete was so poor that it was never better than loose gravel.’ It was decided that a completely new building was necessary and that the old one, which was only thirty-six years old, should be demolished.

To raise funds for the new structure, an appeal was made to Old Marlburians and friends of the school. The work of pulling down Blore’s chapel began about two months after Garner had written to Thomas about its hopeless state, and for the next two years the College had to worship in ‘Upper School’, a large hall which served as a temporary chapel. It was in this building that for the first time those senior masters who were not ordained were allowed to preach sermons, presumably because the building was not consecrated. To accommodate the classes which were normally taught in the building, a structure known as the ‘Tin Tabernacle’ was erected in Court.

With a final cost of £31,000 the new building was erected on the old site by the contractors Messrs Stephens and Bastow, their first of many jobs for Bodley and Garner. The architects expected careful supervision of their work and the clerk of works at Marlborough was David Knight, described by Bodley ‘as a good man ... & used to our work. His terms are three pounds a week.’ Michael Hall has noted an interesting letter written from Garner to Bursar Thomas reflecting the degree of care which was expected of the builders over the stone window tracery: ‘If the tracery is not worked nicely, without ripples, it will look very bad, and we have told Mr Stephens that we wish it worked on the ground where it can be overseen by the clerk of works.’ Stephens and Bastow used much of the first chapel’s Wiltshire sarsen stone in its construction, but they completed the building with ashlar dressing, and the new apse, supported by flying buttresses above the low side chapels is built entirely of Bath Stone.

Marlborough College Chapel: Architecture and History 30

Original from Building News, 3rd December 1886

The chapel, which has an external length of 178 feet and an internal height of 60 feet, was designed to hold a congregation of 900. It was built in Bodley and Garner’s interpretation of late Decorated Gothic and it is not an exact copy of a fourteenth-century style. The apse contrasts markedly with the flat east ends for which the firm became well known, notably those of their masterpieces St Augustine’s, Pendlebury and Holy Angels, Hoar Cross.

At Marlborough, Bodley was determined to increase the focus on the altar by creating a narrow, soaring chancel, in contrast to the broad new nave and indeed the blunt east end of Blore’s demolished building. Mention was made of the restrictions presented by the site determining the shape of the east end, but it is hard to understand what these limitations were. The plan was also influenced by circulation

space required for large number of communicants who could return to their seats by way of the small sanctuary aisles. Marlborough Chapel’s first historian, Newton Mant, commented on the German appearance of the apse, and indeed European Franciscan and Dominican buildings did influence Bodley and Garner. The examples of the Dominican churches of St Blaise at Regensburg and St John the Evangelist (the Predigerkirche) at Erfurt have been cited by Michael Hall, as has Gerona Cathedral in Spain. Bodley was certainly influenced by the architecture of Albi Cathedral when he built St Augustine’s Pendlebury and although Marlborough’s Chapel does not have the same internal buttresses, the thick wall structure and the great single space may have been influenced by Bodley’s knowledge of this great building in south-west France and perhaps other Languedocian aisle-less naves.

Correspondence between Bodley and Garner and Bursar Thomas reveals how much work the practice had to deal with at this time. Bodley was not always an efficient administrator and on one occasion communication broke down. On 23rd July 1885 Garner wrote to Bursar Thomas about the confusion over the cost of the stained glass:

I do not think the firm can be justly charged with neglecting a letter not addressed to it. If people write to Bodley alone they must take the consequences ... my friendship with Bodley is nearly as old as yours, but his best friends cannot call him a good correspondent.

Marlborough College Chapel: Architecture and History

Marlborough College Chapel: Architecture and History 32

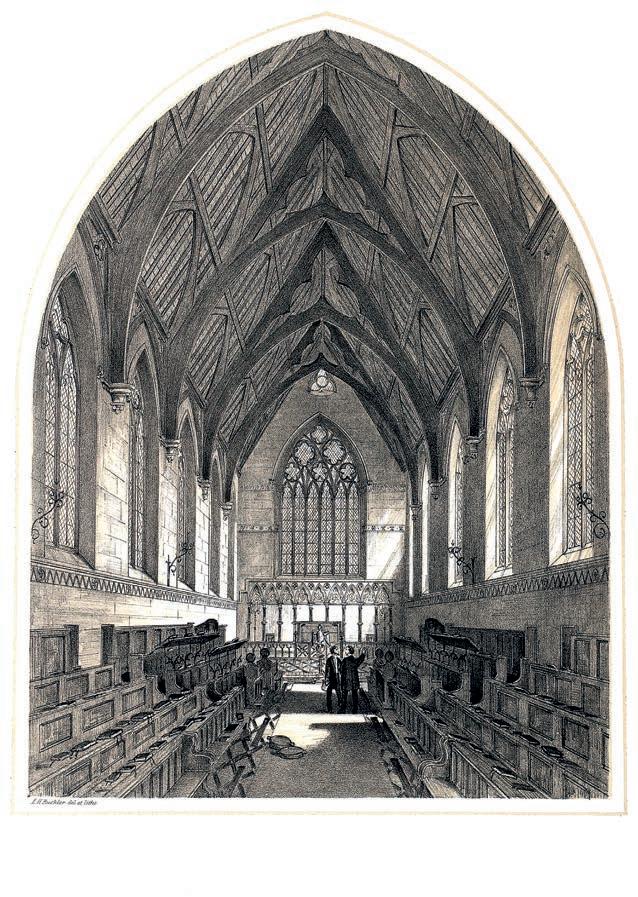

The interior of the Chapel looking east

Garner had difficulties coping with the great workload and suffered from poor health. At this time, he was rushed off his feet by the first competition to design Liverpool Cathedral, which he was working on without Bodley’s assistance. On the 21st of November 1885 he wrote to Thomas about his frustrations and commented that he was half distracted with the cathedral designs. Two days later he declared in another letter he would never again enter an architectural competition.

The interior of the Chapel is one of the great achievements of nineteenthcentury church architecture. Remarkably, the design evolved as the building was being constructed, with a significant alteration being made to the design in April 1885, when the building had already been roofed. Garner proposed stone arches along the internal wall of the forty-feet wide nave to make the walls appear thicker, to ‘give the depth and shadow that are wanted to make the interior look well: and besides, the roof will not be so wide and we will get a taller and more striking proportion.’ This was an expensive decision which came with a long list of extras, pushing the final price well above the original contact price of £22,067.

33 Marlborough College Chapel: Architecture and History

Bodley disliked accounts and kept none, but he had a way of persuading his clients to agree with his wishes. The juggling of the finances must have been a very complicated and frustrating task for Bursar Thomas, but he was equally as committed to making the building as noble as possible.

The repeated arches of the revised design for the nave establish a strong visual rhythm which directs the eye to the narrow chancel and the reredos. The tierceron stone vault of the apse is crowned by a boss depicting an angel bearing the College’s crest. This is placed directly above the high altar. The treatment of the east end presents a marked contrast to the nave, with its broad transverse arches and high wooden barrel vault, decorated with many carved bosses. Right the way along its length on both sides run the words of the hymn

Te splendor et virtus Patris written by the ninth century Archbishop of Metz, Rabanus Maurus, which he dedicated to St Michael. Much care was taken over this painted work, some of which was designed by a young Ninian Comper, the great church decorator who was to return to work in the Chapel to embellish the reredos over sixty years later.

Marlborough College Chapel: Architecture and History 34

The interior of the Chapel looking west

35

Marlborough College Chapel: Architecture and History

The wooden panelling above the stalls was made by William Wilmut of Bristol, a firm well-known to the contractors Stephens and Bastow, and who undertook some important work, notably at the National Gallery in London. House crests and many other motifs appear, and the decorative work above the return stalls for senior teachers at the west end of the building is particularly fine. There are some similarities in the work at Marlborough with the frame made for Spencer Stanhope’s work at Holy Trinity in Florence, including the parcel-gilt grapevine and the five petalled florets. It is also comparable with the wooden parcel-gilt pulpit for the Spencer Stanhope family church at Cawthorne in Yorkshire, which Bodley restored in 1875. Some woodwork in the Chapel was undertaken by H. R. and W. Franklin, an Oxfordshire-based firm which had been favoured by Bodley and Garner since the early 1870s and they remained their carvers of choice. Working first for George Edmund Street in the 1860s, when he was diocesan architect for Oxfordshire, the firm gained a national and indeed an international reputation, producing work for Bodley’s Hobart Cathedral in Tasmania.

Marlborough College Chapel: Architecture and History 36

Following the example of the previous chapel, pews in the new chapel are collegiate and face inwards rather than to the east to emphasise the corporate nature of school life. However noble this intention, having boys facing one another was occasionally as conducive to irreverence and daydreaming as it was to piety and unity: the young John Betjeman recorded in Summoned by Bells how he worshipped only the athletes, ranged in the pews opposite. The masters then, as now, sat in stalls beneath the paintings and the memorials, while the Master and senior staff flanked the entrance. The most senior pupils sat in the higher pews and each row was led out by the head of a house. In chapel and outside chapel, life at the school was strictly hierarchical.

37 Marlborough

College Chapel: Architecture and History

Marlborough

38

College Chapel: Architecture and History

Bodley and Garner’s fine organ case was reinstated in the new building to the north of the choir, instead of at the west end. The gallery which was built in the new building had been designed as an organ gallery, but it was decided this should be used for additional accommodation. The first chapel organ, built by Vowles of Bristol, was acquired in 1853 at the cost of £494. In 1876, at the end of Farrar’s time, a new organ was installed by Forster & Andrews. This was then moved to the chamber at the east end of the new chapel. It was enlarged in 1911, and in 1955 Hill, Norman & Beard completely rebuilt the instrument. Further additions were made but by the beginning of this century, with actions failing, a crowded chamber and much altered pipework, a fresh start was needed. After a wide-ranging search for an organ-builder, a fine von Beckerath was completed in 2007. The Hamburg-based firm has built organs all around the world, but before the Marlborough commission the only other instrument they had made was the neo-Baroque organ at Clare College Cambridge of 1969. The Marlborough instrument is very different. This 62-stop four manual organ was designed to suit French and German music as well as the English romantic tradition.

39 Marlborough College Chapel: Architecture and History

Bodley never regarded himself as a member of the Arts and Crafts movement, although his office was a nursery for this important development and his buildings were noted for the quality of their decoration and handicraft. He was the most respected church architect of the last decades of Victoria’s reign and an important patron of the applied arts. The ecclesiastical fabric and vestment firm which he helped to found, Watts and Co (which still prospers), did much to enhance the reputation of the office as specialists in coloured decoration. At Marlborough, Bodley and Garner produced one of their most important interiors, taking great care over all aspects of its design. It must have disappointed them that its crowning glory, the Spencer Stanhope paintings, proved to be so controversial. In 1879

The Marlburian had commented on ‘the forms of Benozzo Gozzoli, here dashed with a conception which goes back to Giotto, there tinctured with an idea borrowed from Luini or Masaccio’. After their installation in the new chapel The Builder (1886) commented ‘We should have

preferred that English boys should see before them in a chapel something more manly than Mr Spencer Stanhope’s weak and superstitious sentimentalities; but we suppose that is not our business.’ However, the journal was impressed by the building and commented that it was ‘a form of modern architecture (or ancient architecture) in which the architects of this chapel perhaps have hardly their equal among their contemporaries at the present moment.’

Burne-Jones acknowledged that his friend Spencer Stanhope’s work had its faults, but he believed that his colour ‘was beyond any the finest in Europe ... It was a great pity that he ever saw my work or that of Botticelli’s. Though there may be a time for him yet. An extraordinary turn for landscape he had too –quite individual.’ Burne-Jones felt that it was unfortunate that Spencer Stanhope had to leave London, his ‘proper atmosphere’, because of his asthma. Living in Florence had damaged his work because he thought ‘exclusively about old pictures to the extent that he’ll

found his own pictures on them and give up his own individuality. But I love him.’

The paintings at Marlborough may be uneven in quality, but it should be remembered Bodley and Garner stipulated the pictures should be as decorative as possible, harmonise with each other and with the colour scheme of the whole chapel. It was a challenging commission in terms of its scale and the demands made upon the artist. It was conceived to decorate Blore’s building but then had to work in Bodley’s much larger structure. Because there was some dissatisfaction with the work when it first arrived in Wiltshire, Spencer Stanhope agreed to make some alterations to the pictures while the new chapel was being built, and all of the paintings were returned to the artist so their colour could be enhanced, and the damage caused by gaslighting repaired. He took into consideration the change in the colour scheme from the old chapel’s light red and sap green scheme to Bodley’s new greens and browns. To begin with the whole series was returned to Spencer Stanhope’s

Marlborough College Chapel: Architecture and History 40

Harley Street home, but the work took longer than expected because of the damage (which included a hole in one work), and four of the paintings were sent to a studio in Brighton which he had hired. He was unable to complete the work there in time and so he sent all the paintings back to Florence.

The alterations to the paintings during the new chapel’s construction caused considerable concern. Evidently, the possibility of employing another artist was considered but Bodley felt it was important the commission for the unfinished pictures should not be given to anybody else, for the sake of unity. In his view, Burne-Jones was the only artist whose work would blend with the paintings completed by Stanhope. On the 23rd of July 1885 Bodley wrote to the Bursar to say that he was hoping for a real improvement in the colour of the work. At this point the commissioning of further paintings was considered, but Bell was not keen. Bodley suggested that a difficult situation might be avoided if the work on the pictures was

delayed, and he suggested that funds might be diverted to build a great reredos. He stressed that this idea was of a private nature, presumably fearing that the artist might be upset still further if he heard that he personally had suggested such a scheme. The following day the Master gave his consent, although he commented that the matter of whether the College could afford a reredos was a different matter. Spencer Stanhope continued to paint, unaware of all these deliberations and charging nothing for his work apart from expenses, but the progress was slow and Bodley wrote on the 9th of July 1886 that one or two of the pictures had been ‘unpainted’ and the artist refused to let the College have these. Seven of the well-travelled paintings were not ready in time for the Consecration service of September 1886 and it was not until the summer of 1887 that the whole series was installed in the Chapel, a situation which upset the College authorities, but it is clear that the additional work and the logistical complications caused Spencer Stanhope considerable difficulties.

41 Marlborough College Chapel: Architecture and History

Bell wanted something to counterbalance the painter’s angels’ lack of ‘manliness’, and the new sculpture for the building was intended to do this with national and military imagery. The exterior of the apse is adorned with statues of St Michael, St Gabriel and St Raphael, and beneath these there are representations of St George, St Andrew, St Patrick and St David, the patron saints of England, Scotland, Ireland and Wales: these lower figures were given to the College by the tradesmen of the town. The tall organ chamber to the north of the Chapel is adorned with more patriotic imagery, with shields bearing the arms of England, Scotland Ireland and Wales, and the Diocese of Sarum and Province of Canterbury are

also represented. The figures were carved by the Scottish sculptor John McCulloch, who was based in Kennington, South London. His work adorns the façade of Dora House on the Old Brompton Road in South Kensington, designed by fellow Scott William Flockhart, now the home of The Royal British Society of Sculptors. McCulloch worked for Bodley and Garner at Pembroke College Cambridge, and Magdalen and St John’s College Oxford as well as Bodley and Garner’s great church of Holy Angel’s, Hoar Cross in Staffordshire. McCulloch died when he was only thirty-nine. His best-known pupil was Laurence Turner, an Old Marlburian who became the Master of the Art Workers Guild in 1922. Turner undertook work for Bodley and Garner and he was a key figure in the sensitive restoration of many important old buildings. He was responsible for carving William Morris’s tomb, and he returned to the College to work on the carving needed for the Memorial Hall, which records the lives of those who fell in the First War.

42

The great reredos which Bodley and Garner designed for the Chapel, modelled on late medieval German examples, is an extraordinary feature of the building. Given the unusual nature of the apse it is surprising that its construction had not been considered before 1885: the east end would have been very severe without it. However, given the correspondence of that year, a painted east end might well have been the original intention. In the wake of the difficulties with Spencer Stanhope there seems to have been a change of plan. The reredos was another late and expensive addition to the Chapel and almost certainly the result of teamwork by the persuasive Bodley and Thomas. It was carved in Corsham stone by the distinguished firm of Farmer and Brindley, favoured by Bodley and Garner for their most important works. Farmer ended up dealing with most of the administration, but Brindley became a renowned figure, and he was regarded by the famous architect George Gilbert Scott as the most remarkable sculptor he had known. Farmer and Brindley worked on many important Victorian sculptural projects, notably the Albert Memorial and the Natural History Museum. Such was the success of the firm, based in Westminster Bridge Road, that by the 1880s Brindley was sub-contacting much of his work to other sculptors, mostly from abroad.

43 Marlborough College Chapel: Architecture and History

Marlborough College Chapel: Architecture and History 44

Above: The reredos shortly after completion

Right: The reredos today

45

Carved angel heads can be found throughout the Chapel, and it was thought fitting that angels should adorn the reredos, continuing the theme of the paintings. The youthful angels surround the central depictions of the nativity and the crucifixion. Some of them wear armour and resemble knights, reflecting the importance which was attached to chivalry in Victorian England. Many school sermons were preached on knightly virtues in public school chapels, although earlier in the century Thomas Arnold had spoken about the dangers of obsessions with codes of behaviour: he believed notions of chivalry could set personal allegiances before God and the concept of honour before justice. In the age of the Gothic Revival, however, notions of chivalrous conduct and individual loyalties were encouraged by the public schools. Although Bell was happy the figures on the new reredos surrounding the central scenes should be angels, they should not be depicted with the instruments of the Passion. Instead, they should be angels of the Powers, Principalities and Virtues, and shown as warriors who were more masculine than Spencer Stanhope’s angels.

Marlborough College Chapel: Architecture and History 46

An angel in armour

Carved figures in places of worship caused considerable controversy in the last few decades of the nineteenth century, but nevertheless some remarkable work was undertaken, such as the careful restoration by George Gilbert Scott of the reredos of All Souls College, Oxford, which brought the great medieval screen back to something like its original form. In 1885 work commenced work on restoring the reredos of Winchester Cathedral with the recreation of the figures destroyed in the Reformation, a task which was undertaken in the face of bitter criticism. The completion of the central crucifixion scene by Bodley and Garner in 1896 was particularly contentious, and having just converted to Roman Catholicism, Garner felt it best to dissolve his partnership with Bodley. The work on the Marlborough reredos ten years earlier would have been seen by some as dangerously ‘High’ for a Broad-Church school.

At this time, however, some felt that fine figurative monuments and decoration reflected not only the glory of God but also the dignity

of humanity, underlining the importance which was attached to the doctrine of the Incarnation. David Newsome has described how in the late Victorian Anglican church the theology of the Incarnation emphasised the way in which humankind had been ennobled and elevated by divine grace, so the works and writings of men and women could reveal God’s purposes, because in some way the divine was reflected in them. This confident belief fed into the architecture of the time, with decorative secular imagery appearing in ecclesiastical architecture and furnishings. School chapels of the age are filled with heroic figures and symbols of places and people deemed worthy of respect and emulation. Incarnationalism, which often fused the works of Plato, the Gospel of St John and the poetry of Robert Browning, was promoted by such eminent clergy as Charles Gore, Henry Scott Holland and Brooke Foss Westcott, the future Bishop of Durham, to whom Mrs Bell, the Master’s wife, wrote about the need to have a great reredos in the Chapel. Westcott, a celebrated preacher,

was a canon of Westminster and a colleague of the two former Marlborough Masters there, Archdeacon Farrar and Dean Bradley.

Bodley and Garner wished the reredos to be painted together with the chancel vault to draw attention to the east end, but the stone was not sufficiently dry for it to be decorated by the time of the consecration. Some colour was applied shortly afterwards but the present elaborate scheme was not executed until 1951.

James Welldon, the Headmaster of Harrow, once declared that his school’s chapel was not so much a monument as a biography. To an equal degree the memorials in Marlborough Chapel recall the achievements of those who have been associated with the College, and of course the windows also tell stories. For the new windows of the chancel Bodley chose Burlison & Grylls, a firm which he had promoted, partly because he did not approve of the increasingly High Renaissance character of Burne-Jones’s stained glass. Their best-known window is perhaps the southern rose of Westminster Abbey. Some of the Chapel’s glass was inherited from Blore’s chapel. The first window to the west on the south side of the building is a memorial to Cotton by Saunders & Co, and there is glass by Preedy, Powell & Sons, and Clayton & Bell. The William Morris window was adapted to fit the new tracery in one of the southern windows.

47 Marlborough College Chapel: Architecture and History

To the north of the Chapel’s chancel is a small chapel which has an important window, which was the gift of Bradley. This part of the building is almost a shrine to the influence of Thomas Arnold. Beneath this window there is an inscription which states the glass is a memorial to Bradley’s predecessor as Dean of Westminster, Arthur Penhryn Stanley, another of Arnold’s greatest pupils and his first biographer. He was a member of Marlborough’s Council between 1854 and 1880. Bradley was one of Stanley’s best friends and in turn his biographer.

Arthuri Penrhyn Stanley Decani

Westministriensis Huius Collegii e Concilio Defletissimi amici amicus in memoriam Hanc fenestram posuit Georgius Granville Bradley Dec. West. AD 1887

‘This window was placed here in memory of Arthur Penrhyn Stanley, Dean of Westminster, a member of the Council of this College and a much-lamented friend by his friend George Granville Bradley, Dean of Westminster. AD 1887.’

Colin Fraser has observed that this contains a lovely example of a polyptoton − the repetition of a root word in a different form − amici amicus − which captures nicely the closeness of their friendship.

Left: The Dean Stanley window Right: The Great West window

Marlborough College Chapel: Architecture and History 48

The great Te Deum West window in Chapel, some of which used to be in the East window of the old chapel, is fine work by Clayton & Bell, set in tracery which Bodley based on the design of the west window of Durham Cathedral. The glass in the lower part of the window is particularly impressive, with beautiful depictions of plants, fishes in the sea and cattle. In late afternoon summer sunshine, the whole ensemble is particularly striking and the colour of Bodley’s interior, the greens and browns admired by Betjeman in Summoned by Bells, is transformed in a golden

blaze. The partnership of John Clayton and Alfred Bell was formed while they were both working in the practice of George Gilbert Scott. By 1861 they had moved into large premises in Regent Street, London, where they became one of the most prolific and proficient workshops of English stained glass during the latter half of the nineteenth century. With three hundred employees, night shifts were worked to fulfil the large number of commissions. Their windows can be found throughout the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada, Australia and New Zealand. They made the West Window of King’s College Chapel, Cambridge in 1878, but probably the most significant commission was to design the mosaics for the canopy of the Albert Memorial

Eight of the twelve Spencer Stanhope angels from the East wall of Blore’s chapel now flank this window. A drawing by the architects shows that it had been intended all twelve angels should adorn the eastern walls of the new chancel arch, but here they would have been cramped and some would have been obscured by the organ case.

Marlborough College Chapel: Architecture and History

Marlborough College Chapel: Architecture and History

51

Ensemble of Angels North side of West Window

Ensemble of Angels South side of West Window