What is the Alhambra of Granada?

Considered the main reference of Hispanic-Muslim architecture, the Alhambra of Granada is the only Islamic palatine city that has remained practically intact until today. From the thirteenth to fifteenth century, the Alhambra was the official residence of the Nasrid sultans, who were behind the construction of numerous gardens and palaces to host their many activities.

Amongst the most emblematic spaces of the site are the Mexuar, the Palace of Comares and the Palace of the Lions, which contain some of the best samples of Islamic art. Owing to its historical and cultural value, the Alhambra of Granada was declared a World Heritage Site by Unesco in 1984.

The history of the Alhambra of Granada

During the thirteenth century Muslim presence in the Iberian Peninsula declined sharply due to rivalries between the different families that wanted to rule the territory and the effectiveness of the expansionist policy undertaken by the Christian monarchs.

The last bastion of Islamic power was the Nasrid kingdom, founded in 1232 by Muhammad I (also known as Ibn Al-Ahmar, “the son of the red”) who managed to retain its independence by means of one-off smart policy alliances with the Spanish Royal Crown and North African leaders. In 1238 the Sultan established the headquarters of his court in Granada, on some ancient fortifications that existed on Sabika Hill, one of Sierra Nevada’s foothills.

It was at this time that the Alhambra was built, a large fortified enclosure which, thanks to the refurbishments carried out by successive Nasrid sultans, steadily expanded until it formed a complex urban network, becoming one of the most imposing palatine cities of the time, equipped with luxurious Nasrid palaces, numerous administrative offices, mosques, schools, barracks, landscaped gardens, orchards, baths and workshops.

The Alcazaba of the Alhambra

Since its origins, the Alcazaba was the main centre for monitoring the Alhambra of Granada. This function was not only reflected by the strategic location of its towers, which, connected by means of a wall, offered a privileged view of the surrounding territory, but also by the presence of the neighbourhood designed for the military contingent that was responsible for defending the Sultan and his court.

Based around a longitudinal street, this urban area consisting of dwellings, warehouses and stores, amongst other buildings, guaranteed the self-sufficiency of the Alhambra of Granada, as well as the ability to react to potential attacks.

The Nasrid Palaces of the Alhambra of Granada

The kingdom of Granada in the fourteenth century underwent a great period of growth and prosperity in all areas. In the Alhambra, this cultural effervescence materialised in the construction of the three spaces that constitute the Nasrid Palaces: the Mexuar, the Palace of Comares and the Palace of the Lions.

Projected at different times in the northern area of the palatine city (an area well protected by the strong outer wall and the uneven terrain on the left bank of the River Darro), these palaces, landmarks of Islamic art, became the setting for the Alhambra of Granada sultans’ busy official duties as well as their private family life.

The most prominent craftsmen of the time participated in their design, refining the resources and techniques developed by their predecessors in order to bring Nasrid architecture to its maximum splendour, leading to works of unparalleled beauty, which even aroused the admiration of the Christian monarchs.

The Mexuar, a palace in the Alhambra of Granada

Originating from a Nasrid family settled in the city of Malaga, Sultan Ismail I governed the kingdom of Granada from 1314 to 1325, a period marked by internal stability and economic prosperity. This favourable context led to the construction of a palace situated in the northwest corner of the Alhambra of Granada, on land that was very close to the Alcazaba.

The architectural structure that has survived consists of two large courtyards and the Mexuar Hall, which gives its name to the site and which refers to the council of viziers who assisted the Sultan in legislative tasks. With the construction of the Comares Palace and the Lion Palace, the Mexuar site probably lost its original residential use and focused more on activities of a bureaucratic and judicial nature, but nonetheless remained a vital space for the daily functioning of the Alhambra.

The Comares Palace

The kingdom of Granada experienced one of its most prosperous periods under the rule of Yusuf I, who came to the throne in order to substitute his brother Muhammad IV, assassinated in the year 1333. Described by Arab historians as a meditative leader of calm character, the seventh Sultan of the Nasrid dynasty was able to ward off attacks from Christian troops as well as the influence of the North-African emirs, guaranteeing a prolonged period of peace that was taken advantage of in order to provide the city with diverse public installations and promote cultural development.

With the Alhambra, the monarch launched an ambitious building program that culminated in the creation of a new Nasrid palace on land adjoining the Mexuar. Structured around a rectangular courtyard and presided over by a tower that contained the Throne Room (the most important room of the palatine city), the area known as the Comares incorporated the most characteristic elements of Hispano-Muslim residences.

Likewise, it became one of the chief testimonies of royal power by means of its allegorical decoration, completed by the son and successor of Yusuf I, Muhammad V.

The Palace of Lions

Aiming to demonstrate the greatness of his government, Muhammad V renovated the grounds of the Mexuar and completed the décor of the Comares Palace, though his most ambitious project was the building of the Palace of the Lions, where the Sultan had his quarters, as well as other more public rooms which accommodated all kinds of festivities and formal events.

With the idea of creating a suitable environment for these functions, a program of a highly refined ornamental nature was developed, which made the palace the synthesis of all the achievements of Nasrid art. Designed around the Lion Courtyard, the site or area designed by Sultan Muhammad V was named the “Happy Garden”, possibly because it was constructed on ancient gardens.

This name also stressed the Eden-like nature of a space that has very often been compared to a stone oasis. In fact, various architectural elements correspond to this idea, starting with the columns that resemble palm trees that border the Court of the Lions, up to the water gutters that are reminiscent of garden streams, on to the gallery pavilions that can be likened to Arab tents.

The Generalife

The construction of the Generalife site probably began in the last third of the thirteenth century on the initiative of Muhammad II, the son of the founder of the Nasrid dynasty. Enlarged several times during the Muslim period, the property was established at a safe distance from the Alhambra, in order that the Sultan could have the privacy he required, but which also included rapid and uncomplicated access to the palatine city if his presence was required in court.

Also, due to its geographical situation, on a hillside, the Generalife was distributed into several terraces, a layout that included marvellous views of the surrounding landscape with interesting plays of perspective.

Christian chambers in the Alhambra

Following a decade of war, in 1492 the Catholic Monarchs conquered the city of Granada, culminating their project which was to take over all the territories on the Iberian Peninsula that had been under Muslim control. As a sign of their appreciation of the Nasrid architectonic legacy and eager to provide lasting evidence of their military victory, the Castilian-Aragonese monarchs financed a series of architectonic refurbishments that were designed to guarantee the conservation of the Alhambra of Granada.

The grandson of the Catholic Monarchs, Emperor Charles V, remained faithful to the idea of safeguarding the palatine city as a symbol of royal power, even though he was more ambitious than his predecessors by planning the construction of a new palace to become the headquarters of his court.

In order to accommodate the monarch whilst work on his future residence was being carried out, between the years 1528 and 1537 diverse rooms were built around the Comares Palace and the Palace of the Lions, connected by means of a corridor and overlooking an irregularly shaped courtyard.

Charles V Palace

Initiator of the Hapsburg dynasty in Spain and responsible for the most important empire of his time, Charles V first came into contact with Granada in 1526, when he spent his honeymoon there after celebrating his marriage in Seville with Isabella of Portugal.

Despite having grown up in the Netherlands, the Catholic Monarchs’ grandson quickly grew to appreciate how symbolically important the former capital of the Nasrid realm was for the Spanish Crown and, amazed by the beauty of the Alhambra, decided to erect his own residence in the palatine city, which was to convert into a symbol of religious unity at a time marked by conflicts with the Ottomans and by divisions caused by the Protestant Reformation.

The design of the Charles V Palace –identified by the name Casa Real Nueva (New Royal House), in contrast to the Casa Real Vieja (Old Royal House), referring to the buildings of Muslim origin such as the Nasrid Palaces– was carried out by Pedro Machuca. Trained in Italy along with artists such as Michelangelo, the architect devised a Renaissance monumental style edifice, incorporating a circular courtyard within a square ground plan. Defrayed by taxes paid by Moriscos, the work started in 1527, but could not be completed on time.

Machuca died when he had only erected a part of the exterior, whilst Charles V hardly had time to concern himself with the progress of the work due to constant political and economic conflicts he had to tackle. The Emperor’s successors let the project languish, and it wasn’t until the twentieth century that pending building work could be finished on the Charles V Palace, which adopted a new use as a museum.

A detailed visual book about the Alhambra of Granada

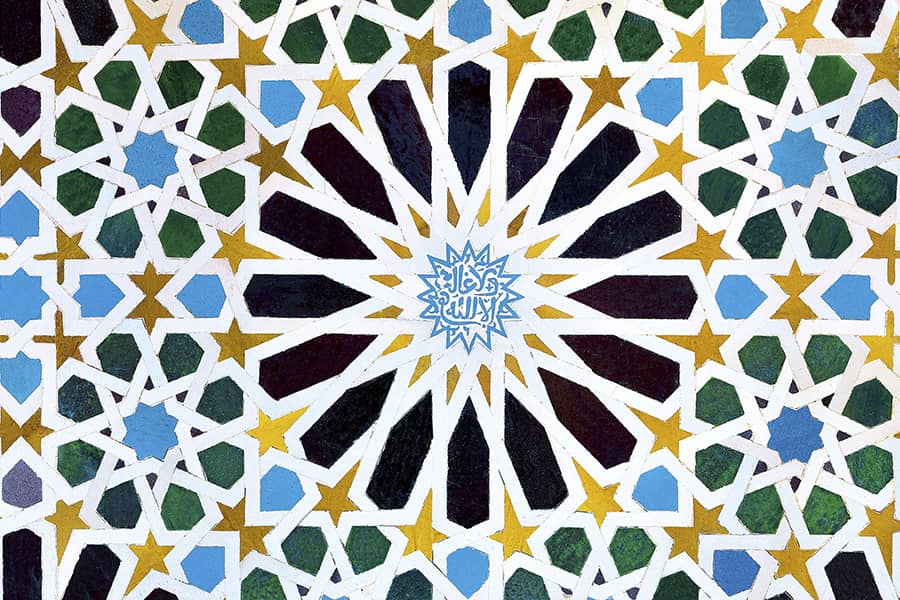

The Alhambra of Granada constitutes the most valuable testimony of Muslim presence in the Iberian Peninsula. The ceramic work, the coffered ceilings and plasterwork that decorate the rooms show the perfection reached by Islamic architecture. The incorporation of plasterwork, coffered ceilings and ceramic work are one of the characteristics of the Alhambra, and show the perfection reached by Islamic architecture.

Discover the Alhambra in this book that unveils the Alhambra’s singular beauty. It includes more than 500 photographs, illustrations and 3D infographics that help the reader explore this monumental site in greater detail. Published by Dosde.