Like this post? Help us by sharing it!

Japanese art is one of the world’s greatest treasures. From unique styles of ink painting and calligraphy, through innovative ceramics and magnificent woodblock prints, the contributions of Japanese artists are unmatched.

In this two-part series we at Japan Objects will introduce you to some of the stories behind Japanese art and how it came to be. In this article we will look at traditional art forms. You will learn why nature has always been central to the Japanese way of life, and how the Edo era produced some of the most exquisite paintings of beautiful women.

The Origins of Japanese Art

The Great Wave off Kanagawa by Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849) is undoubtedly one of the most famous works of Japanese art. It is no coincidence that the theme of this much-loved woodblock print is the formidable power of nature, and that it contains the majestic Mount Fuji.

Nature, and specifically mountains, have been a favourite subject of Japanese art since its earliest days. Before Buddhism was introduced from China in the 6th century, Shinto was the exclusive faith of the Japanese people. At its core, Shinto is the reverence for the kami, or deities, who are believed to reside in natural features, such as trees, rivers, rocks, and mountains.

In Japan, nature is not a secular subject. An image of a natural scene is not just a landscape, but rather a portrait of the sacred world, and the kami who live within it.

This veneration for the natural world took on many layers of new meaning with the introduction of Chinese styles of art – along with many other aspects of Chinese culture – throughout the first millennium.

This meticulous Heian era (794-1185) painting is the oldest surviving Japanese silk screen, an art form itself developed from Chinese predecessors. The style is recognisably Chinese, but the landscape itself is Japanese. After all, the artist would probably never have been to China himself.

The creation of an independent Japanese style of art, known as yamato-e (Japanese pictures), began in this way: the gradual replacement of Chinese natural motifs with more common homegrown varieties. Japanese long-tail birds were often substituted for the ubiquitous Chinese phoenix, for example, while local trees and flowers took the place of unfamiliar foreign species.

As direct links with China dissipated during the Heian period, yamato-e became an increasingly deliberate statement about the supremacy of Japanese culture. Zen, another Chinese import, was developing into a rigorous philosophical system, which began to make its mark on all forms of Japanese art.

Zen monks particularly took to ink painting with sumi-e reflecting the simplicity and importance of empty space central to both art and religion. One of the greatest masters of the form, Sesshu Toyo (1420-1506), demonstrates the innovation of Japanese art in View of Ama no Hashidate, by painting a bird’s eye view of Japan’s spectacular coastal landscape.

Tea Ceremony

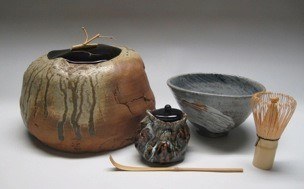

The evolution of the tea ceremony had a profound influence on Japanese art and craft. Well-to-do families had long used social occasions to show off their most sumptuous Chinese tea implements, but this began to change in the 16th century, when aesthetes began to move towards a simpler style.

The popularity of humbly decorated, unpolished, and (most significantly) Japanese tea implements transformed from a trend into a permanent fixture of the Japanese design landscape, through the endorsement of ascendant military leader Toyotomi Hideyoshi and his tea master Sen Rikyu (1522-1591).

The style of craft Rikyu favoured has come to be known as wabi-sabi. The zen-derived concept, while difficult to translate, refers to a philosophy of imperfection and impermanence. It can be seen in the preference for understated earth tones over glittering painted colours for example, and the irregular shapes of hand-moulded ceramics over the perfection of wheel-thrown pots.

Ukiyo-e Prints

The Edo era (1615-1868) enjoyed a long period of extraordinary stability. Edo society was booming and cities expanded on an unprecedented level. Social classes were strictly enforced. At the top there was the samurai serving the Tokugawa government, then the farmers and the artisans, and finally at the bottom of the rank were the merchants.

However, it was often the merchants who benefited the most economically due to their role as distributors and service providers. With new prosperity, goods of all kinds flourished. In particular woodblock prints, ukiyo-e, reached their apex in popularity and sophistication.

Ukiyo-e literally means ‘pictures of the floating world’. In its Edo context, these stunning woodblock prints highlight the cultivated urban lifestyle, fashion and the beauty of ephemeral.

One of the most important purposes of ukiyo-e was to reflect the stylish lifestyles of the Edo urbanites. Merchants were confined to their social status by law and as a result, those with means spent their time in pursuit of pleasure and luxury, such as could be found at the Yoshiwara brothel.

Yoshiwara was a well-known social club that was more than just a brothel; it was a cultural hub for the rich and connected men of the Edo era.

The courtesans of Yoshiwara are stunningly portrayed in ukiyo-e prints; their lavish kimono, hairstyles and make-up painstakingly brought to life. They were the stars of the Edo period, and through these relatively cheap and widely distributed prints their every move was followed religiously by the townspeople in their normal lives.

Kabuki theater was another popular ukiyo-e subject with yakusha-e (actor prints). Images of top-billing actors were frequently reproduced, with prints capturing theatrical scenes with astonishing artistry and detail.

Ukiyo-e prints have been hugely influential. You can see their impact in the paintings of European artist like Monet and Degas, but also in works of modern Japanese artists. Next week we’ll take a look at Japanese art today, and some of the contemporary artists that continue to astonish the world with their innovation and technical brilliance.

About Japan Objects

Japan Objects is an online magazine for culture lovers, presenting the most inspiring Japanese art & design through informative articles and tailor-made travel guides.

Interested in Japanese art? If you are in the UK, we are sponsoring Bristol Museum’s Masters of Japanese prints: Hokusai and Hiroshige landscapes exhibition between 22 September 2018 – 6 January 2019 – see you there!

Take a look at our Art experiences in Japan, or contact our team of Japan experts to find out more.