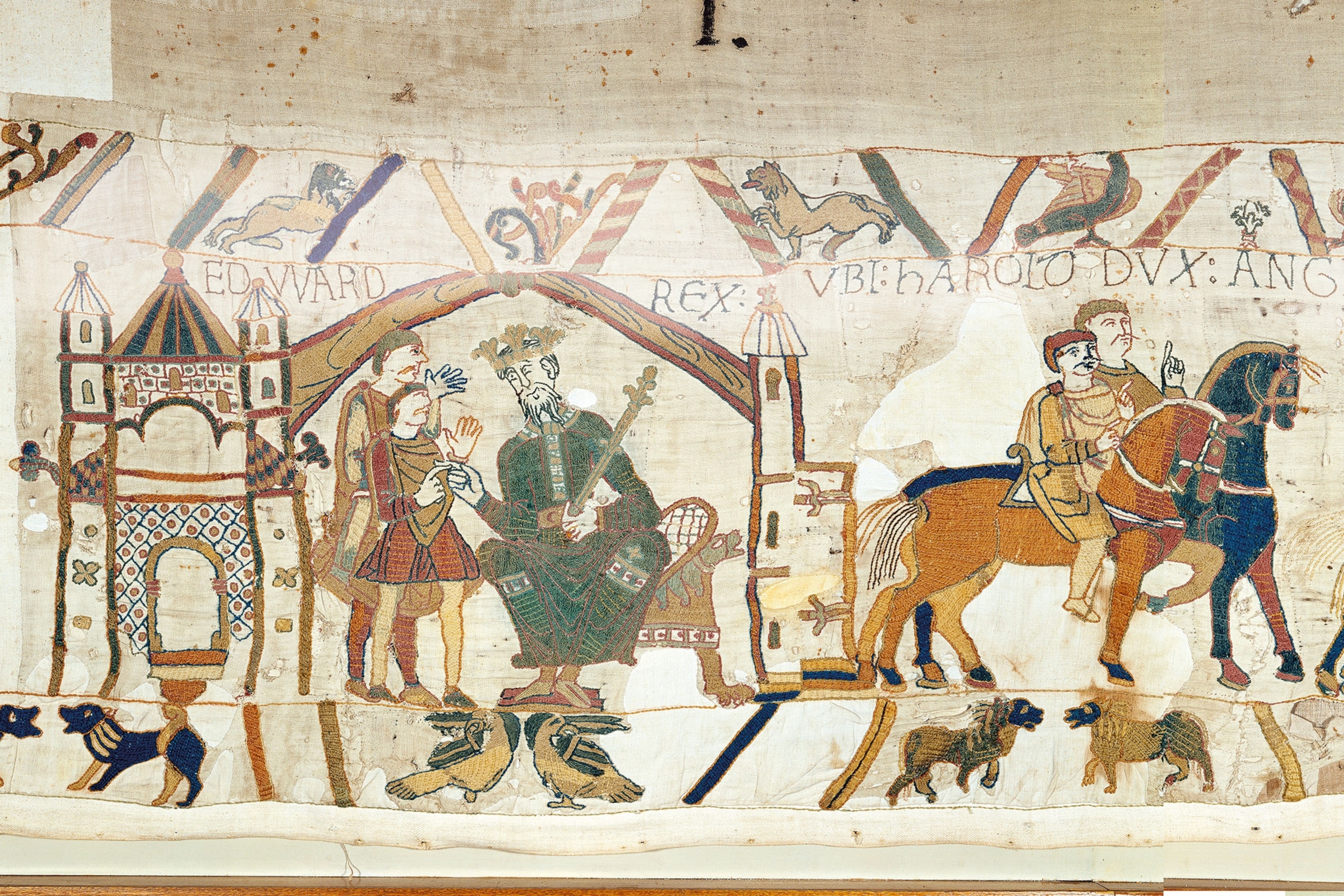

Anglo-Saxon England's defeat unfolds across the Bayeux Tapestry

Measuring nearly 230 feet long, the medieval artwork celebrates William of Normandy's victory in 1066. Historians point to it as masterwork of propaganda.

The date 1066 is imprinted on the minds of generations of British schoolchildren. This was the year that William, Duke of Normandy, defeated King Harold II at Hastings and set in motion some of the most profound political and social changes in English history.

The Norman Conquest imposed on England an entirely new, French-speaking ruling class, a huge stock of new surnames—Warren, Lewis, Sinclair, Boyle, Churchill, to name a few—and planted the seeds of the modern English language. Yet the most vivid chronicle of this upheaval is not expressed in words, but in colored threads across nearly 230 feet of linen.

What is now known as the Bayeux Tapestry is not, in fact, a tapestry at all, but an embroidery of woolen thread stitched on to cloth. Ten colors create rich scenes that recount the story of the fateful clash between William and Harold: Scenes of pomp and diplomacy; a fleet of longboats filled with troops and supplies; and the fury of the battle itself, in which arrows fly and men and horses crash to the soil. The only missing scene is the conclusion, the depiction of William’s coronation as the English king. Captions in Latin label key figures and events. Progressing from scene to scene like a comic strip, the upper and lower bands are richly decorated with marginalia: Scenes from the fables of Aesop or of the pleasures of the hunt.

Produced in the decades following the Battle of Hastings, the tapestry’s association with Bayeux in Normandy, in whose cathedral it was stored for many centuries, suggests that its initiator was Bayeux’s bishop, Odo. Half brother of William, Odo also fought at Hastings. Odo’s massive work was most likely conceived as propaganda for a mass audience, trumpeting the legitimacy of the Norman Conquest through its depiction of the political events leading up to the battle. A knowledge of complex dynastic disagreements helps decode the “plot” of this medieval masterpiece. (Scientists are using lasers to unlock the mysteries of Gothic cathedrals.)

Embroidery by numbers

The Bayeux Tapestry measures nearly 230 feet long by 20 inches high and consists of nearly 60 scenes of woolen thread embroidered on linen. Its scenes are populated by hundreds of warriors, 174 horses, 55 dogs, and 37 ships. Only three female figures are depicted in the tapestry, it was almost certainly stitched entirely by women.

A promise broken

Before the Battle of Hastings, English kings descended from the ninth-century Anglo-Saxon ruler Alfred the Great, considered to be the first king of a united England. Alfred’s successors made dynastic marriages with powerful neighbors, including the nobles of the Duchy of Normandy, which extended in and around the Normandy peninsula in France.

The Normans (whose name derives from “northmen”) were descended from the Vikings of Scandinavia, who marauded the French coast starting in the 800s. The Normans became Christians, adopted the French language from the peoples whom they invaded, and amassed considerable power and wealth.

Dynastic marriages often sow the seeds of future succession crises. In 1002 Aethelred II— also known as “the Unready,” meaning “poorly advised”—married Emma, daughter of the Duke of Normandy. Their son was Edward, who would rule England from 1042 as Edward the Confessor. (These are ten of history's red-hot power couples.)

News from the King

Edward was unable to produce a biological heir, which left him vulnerable to the maneuverings of a powerful nobleman, Godwin, and Godwin’s ambitious son, Harold. Across the Channel, the Duke of Normandy—William—had a strong claim to the English throne through his great-aunt, Emma, who was Edward’s mother.

According to the Norman version of events, King Edward sent Harold in 1064 to assure William that he would inherit the English throne. The mission was fraught: Harold was shipwrecked and taken prisoner by a Norman nobleman before William rescued him. Harold enjoyed William’s hospitality and accepted the hand of his daughter. Harold—according to a single Norman source from the 1070s—swore fealty to William and pledged to support his claim to England’s throne when Edward died. The Saxon version of events differs, and those sources claim that Harold never took this oath.

The scenes shown in the Bayeux Tapestry support the Norman story. They reinforce Norman legitimacy by depicting the solemnity of Harold’s oath-taking and amplify the Norman sense of betrayal at what happened next. For when Edward the Confessor died in early 1066, Harold seized the throne and was crowned Harold II of England in January.

An oath, a betrayal, and a comet

Enraged, William spent months preparing his forces in Normandy and then set sail for England with them in September. A gifted military commander, Harold was squashing a revolt in northern England when he heard of William’s arrival on the Sussex coast. He quickly mustered all the soldiers and supplies he could and headed south, where he would meet his demise at the Battle of Hastings. Following Harold’s death, William the Conqueror became king. (Meet the medieval woman who outwitted and outlasted her rivals in England and France.)

Cloth of conquest

It is generally believed Bishop Odo commissioned English artisans to create the massive narrative work some time around the year 1070. Many scholars believe it was intended for his new cathedral built in Bayeux in 1077, but the precise intention is unknown.

The Battle of Hastings

On display today at the Musée de la Tapisserie de Bayeux in Normandy, visitors can see the tapestry in full, stretching across several pieces of linen cloth. Nearly 60 scenes embroidered in wool thread show kings, armored soldiers, packed longships, galloping horses, and wild beasts. Art historians believe that each panel was first embroidered before being attached to other panels.

The tapestry first appears in the historical record in 1476 in an inventory of cathedral goods. Scholars believe it was displayed one day a year and then stored in the vestry. It isn’t mentioned again until the 18th century. A century later, it went on display in the Louvre in 1803, where Napoleon may have viewed it.

Death on the battlefield

The Bayeux Tapestry remains a potent symbol of conquest. In 1944, ahead of advancing Allied troops, France’s Nazi occupiers took it to Paris but abandoned it there before the liberation of the city. The tapestry, and its chronicle of William’s conquest, resonated with the British troops, given that the D-Day landings took place on Norman beaches. In the Commonwealth war cemetery at Bayeux, a Latin inscription reads: “We, once conquered by William, have now set free the Conqueror’s native land.”

Related Topics

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- Orangutan seen using plants to heal wound for first timeOrangutan seen using plants to heal wound for first time

- What La Palma's 'lava tubes' tell us about life on other planetsWhat La Palma's 'lava tubes' tell us about life on other planets

- This fungus turns cicadas into zombies who procreate—then dieThis fungus turns cicadas into zombies who procreate—then die

- How can we protect grizzlies from their biggest threat—trains?How can we protect grizzlies from their biggest threat—trains?

Environment

- What La Palma's 'lava tubes' tell us about life on other planetsWhat La Palma's 'lava tubes' tell us about life on other planets

- How fungi form ‘fairy rings’ and inspire superstitionsHow fungi form ‘fairy rings’ and inspire superstitions

- Your favorite foods may not taste the same in the future. Here's why.Your favorite foods may not taste the same in the future. Here's why.

- Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?

- The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?

History & Culture

- Meet the ruthless king who unified the Kingdom of Hawai'iMeet the ruthless king who unified the Kingdom of Hawai'i

- Hawaii's Lei Day is about so much more than flowersHawaii's Lei Day is about so much more than flowers

- When treasure hunters find artifacts, who gets to keep them?When treasure hunters find artifacts, who gets to keep them?

Science

- Why ovaries are so crucial to women’s health and longevityWhy ovaries are so crucial to women’s health and longevity

- Orangutan seen using plants to heal wound for first timeOrangutan seen using plants to heal wound for first time

Travel

- 5 of Uganda’s most magnificent national parks

- Paid Content

5 of Uganda’s most magnificent national parks - On this Croatian peninsula, traditions are securing locals' futuresOn this Croatian peninsula, traditions are securing locals' futures

- Are Italy's 'problem bears' a danger to travellers?Are Italy's 'problem bears' a danger to travellers?