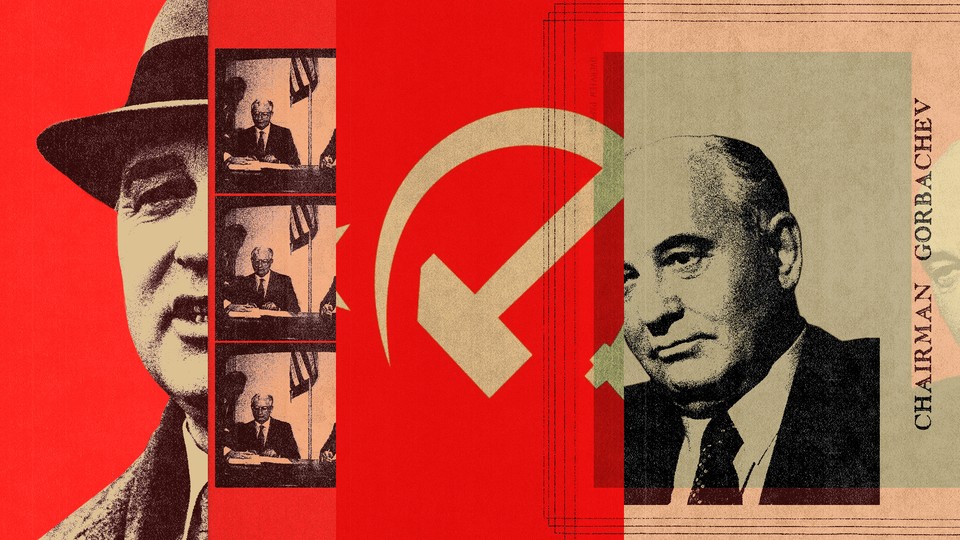

Gorbachev Never Realized What He Set in Motion

Almost nobody has ever had such a profound impact on an era, while understanding so little about it.

The one time I saw Mikhail Gorbachev in public was on November 9, 2014. I can pin the day down because it was the 25th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall. We were in a very large, very crowded Berlin reception room, and he was sitting at a cocktail table, looking rather lost.

Gorbachev had been invited to this event as a trophy, a living, breathing souvenir of the 1980s. He was not expected to say much of interest. The fall of the Berlin Wall had happened by accident, after all; it was not something Gorbachev had ever planned. He had not set out to break up the Soviet Union, to end its tyranny, or to promote freedom. He presided over the end of a cruel and bloody empire, but without intending to do so. Almost nobody in history has ever had such a profound impact on his era, while at the same time understanding so little about it.

Gorbachev was born in Stalin’s Russia, but he began his career during the post-Stalin “thaw,” a moment when it became possible to acknowledge some truths out loud, but not too many. While he was still a student at Moscow State University, one of his closest friends was a Czechoslovak student named Zdeněk Mlynář. Both believed that communism could be reformed, if only the corruption and violence were removed. Mlynář’s convictions led him to become one of the leaders of the Prague Spring, a 1968 movement that started out by calling for “reformed communism” and “socialism with a human face.” That movement was crushed by Soviet soldiers, proving that corruption and violence were intrinsic to a system with no human face. Even cautious Czech reformers could not remove them so easily.

Still, the language of “reformed communism” continued to appeal to Gorbachev, who revived it when he became leader of the Soviet Communist Party in March 1985. But although he knew that Soviet society was stagnant and Soviet workers were unproductive, he had no idea why. In fact, his first instinct was not that the system needed democracy, or even free markets. Instead, he thought: Russians drink too much. Just two months after taking power, he restricted the sale of vodka, raised the drinking age, and started digging up vineyards. By some accounts, the resulting loss of tax income to the Soviet budget, plus the dramatic shortages—people were buying sugar and other products in bulk to make moonshine at home—were the tipping point that sent the Soviet economy into its final death spiral.

Real change had to wait until the Chernobyl nuclear catastrophe of April 1986. News of the accident was initially hushed up, just as bad news was always hushed up in the U.S.S.R. Hundreds of thousands of Ukrainians were allowed to march in the Kyiv May Day parade even as radioactivity spread silently across the city. But the scale of the disaster finally convinced Gorbachev that the real problem with his country was not alcohol, but its obsession with secrecy. His solution was glasnost—openness—which, like the anti-alcohol campaign, was originally meant to promote economic efficiency. Open conversation about the Soviet Union’s problems would, Gorbachev believed, strengthen communism. Managers and workers would talk about what was going wrong in their factories and workplaces, find solutions, fix the problem. No deeper reforms were needed, as he told a group of party economists early on: “Many of you see the solution to your problems in resorting to market mechanisms in place of direct planning. Some of you look at the market as a lifesaver for your economies. But, comrades, you should not think about lifesavers, but about the ship, and the ship is socialism.”

But once glasnost became official policy, once Soviet citizens could talk about whatever they wanted to talk about, factory efficiency was not their first choice of topic. Nor did they want to rescue the sinking ship of socialism. Instead, there was an explosion of debate and discussion about the past, about the history of mass arrests and mass murders, about the Gulag and Soviet political prisons. Historical accounts, memoirs and diaries that had been hidden in desk drawers, raced off the printing presses and became best sellers. Newspapers printed stories of sleaze and mismanagement in the economy, politics, culture, and everything else. Calls for the creation of a different kind of society, a more democratic society, a more law-abiding society, began immediately. The economists whom Gorbachev had silenced started openly talking about the end of central planning. Poles, Czechs, East Germans, Ukrainians, Balts, Georgians, and others then in the Warsaw Pact and the Soviet Union itself all began talking about the end of the empire too. Contrary to the retrospective Putinist historiography now prevalent in Russia, the glasnost era was a creative, exciting, hopeful time for millions of people, even millions of Russians.

Gorbachev seemed bewildered, and no wonder. Having lived much of his life at the top of the Soviet nomenklatura, he never understood the depth of cynicism in his own country or the depth of anger in the occupied Soviet satellite states, most of whose inhabitants rejected even the reformed communism of his youth: They didn’t want the Prague Spring; they wanted to join Western Europe. He never understood the depth of the rot inside Soviet bureaucracies or the amorality of the bureaucrats. In the end, he wound up racing to catch up with history, rather than making it himself.

Because he did not understand what was happening, Gorbachev also did not prepare his compatriots for major political and economic change. He did not help design democratic institutions, and he did not lay the foundations for an orderly economic reform. He removed the old system, put nothing in its place, and then seemed shocked and surprised when a Mafia state arose to fill the vacuum. Above all, he did not tell the Russians that their empire was oppressive and hateful to many of its non-Russian subjects, or that its dismantling represented a huge expansion of human freedom. He did not call for a full reckoning with the Soviet past, and no such thing ever took place. Even afterward, he failed to understand the significance of what had happened. After 2014, he repeatedly declared his support for Russian President Vladimir Putin’s annexation of Crimea, an action that helped catalyze the wave of imperial nostalgia that has now brought us the war in Ukraine.

Gorbachev did change some of his thinking, eventually embracing the idea of democracy, a term he was especially happy to use during his career as a wandering elder statesman, the kind who gets invited to anniversary parties in Berlin. He sometimes criticized Putin in public. But in truth, all of Gorbachev’s most significant decisions, his most radical actions, were the ones he did not make. He did not order the East Germans to shoot at people crossing the Wall. He did not offer the Polish communists a bailout as their economy crashed. He did not launch a full-scale war to prevent the secession of the Baltic states, or to stop the Ukrainians from declaring independence, or to prevent Russia from electing its own leadership too. He made some reactionary attempts to slow things down, and people died in the process, most famously in Vilnius and Tbilisi. But he was not as vicious as some of his predecessors and successors, and he did not, in the end, use mass violence to keep the empire together. Nor did he use violence to stay in power himself.

Gorbachev’s inaction brought the world 30 years of relief from the Cold War nuclear standoff, 30 years of time for some genuine reforms to take hold in some parts of his former empire. Although none of the forces he accidentally set in motion prevented Russia from turning back into a tyranny, the end of Soviet Communism could have been far more bloody, far more violent, and far more like the current war in Ukraine. If someone else had been in charge, it might well have been.