They were three days that shook the world - and shook the Soviet Union so hard that it fell apart.

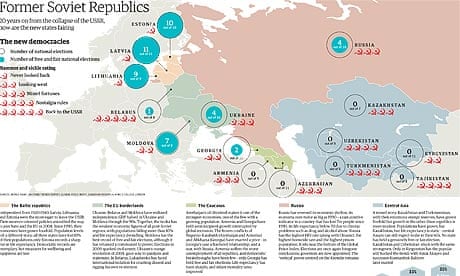

But for better or worse? Twenty years on from the Soviet coup that ultimately ended Mikhail Gorbachev's political career and gave birth to 15 new states, The Guardian was keen to explore just how well those 15 former Soviet republics had performed as independent countries. Our data team mined statistics from sources ranging from the World Bank, the UNHCR, the UN Crime Trends Survey and the Happy Planet Index to compare the performance of the countries. And we combed through the OSCE's reports on every election in each country since 1991 to see where democracy was taking hold - and where it was not wanted.

It was in many senses a traumatic break-up. Like a marriage, there was so much that was jointly owned that it was hard to make a clean break. Industries, military units, whole populations, were scattered across an empire, indivisible. Moreover, the economic crisis that led the USSR to the brink tilted most of the emergent countries into the abyss. GDP fell as much as 50 percent in the 1990s in some republics, Russia leading the race to the bottom as capital flight, industrial collapse, hyperinflation and tax avoidance took their toll. Almost as startling as the collapse was the economic rebound in the 2000s. By the end of the decade, some economies were five times as big as they were in 1991. High energy prices helped major exporters like Russia, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan and Azerbaijan, but even perennial stragglers like Moldova and Armenia began to grow...

The Baltic republics

Since 1990, their economies have grown around fourfold, though not without the occasional financial convulsion. Population levels tell a different story though: all three countries have lost at least 10 percent of their populations, and only Estonia has seen a sharp increase in life expectancy. Democratic records are exemplary, but the countries sit surprisingly low on international measures for wellbeing and happiness.

The EU borderlands

Ukraine, Belarus and Moldova, the other European former republics, have endured rather than relished independence. Ukraine and Moldova sustained catastrophic economic contraction through the 1990s when their GDP slumped by more than half. Belarus, under the autocratic rule of Alexander Lukashenko since 1994, suffered less, but taken together, the troika has the weakest economic figures of all post-Soviet regions, and populations have dwindled by more than 10 percent and life expectancy has fallen. Moldova has the best record of free and fair elections, but also became the first Soviet republic to return a communist (Vladimir Voronin) to power. Elections in 2009 sparked civil unrest. Moldova also hosts to one of the post-Soviet space's many frozen conflicts in which Russophones of the Transdniestr region sought secession. Ukraine's democratic turning point - the orange revolution of 2004 - rapidly gave way to paralysis and stalemate, the country deeply divided between russophone east and nationalist west. In Belarus, Lukashenko has faced lengthy international isolation for crushing opposition and dissent and rigging his own re-election.

The Caucasus

Azerbaijan's oil dividend makes it one of the strongest performing economies in the post-Soviet space, and it is one of the few former Soviet republics with a growing population. Armenia and Georgia have both seen incipient growth through the 2000s rudely interrupted by the global recession of 2008/09. The frozen conflicts of Nagorno-Karabakh (Azerbaijan and Armenia) and Abkhazia (Georgia) have exacted a political and economic price, and in Georgia's case a fractured relationship with its dominant northern neighbour Russia has resulted in the only war between former Soviet republics (2008). Armenia suffers from the worst unemployment of all 15 republics, and democratic breakthroughs have been few - only Georgia has held free and fair elections. Still, life expectancy has risen sharply across the region, and infant mortality rates have been reduced impressively.

Central Asia

A mixed economic story: Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan, with their enormous hydrocarbon reserves, have expanded their economies more than 400 percent over the period; growth in the other three republics, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan has been more modest. Populations have grown in all republics bar Kazakhstan, but life expectancy has barely budged: central Asians can still expect to die in their 60s. And although these are the happiest post-Soviet republics, according to the Happy Planet Index, not one has held a genuinely free or fair election since 1990; central Asia is where elections are deferred or else won with 99 percent of the vote by dictators who lock up their opponents and even ban ballet and name a month of the year after their mother (Turkmenistan). In terms of leadership, Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan are not post-Soviet at all: they have simply stuck with the strongmen who led them out of the Soviet Union. Turkmenistan did the same until he died in 2006, while Tajikistan's Emomali Rahmon (Rahmonov during Soviet times) has run his republic uncontested since 1992. Only in Kyrgyzstan has popular will bucked the trend: Soviet-era leader Askar Akayev was ousted in 2005, as was his successor Kurmanbek Bakiyev five years later.

Russia

Under Vladimir Putin, Russia has reversed its dramatic economic decline such that its economy is now twice as big as it was in 1990 - and four times bigger than in 2000. But that is a rare positive indicator in a country that has lost 7 million people since 1991, its life expectancy persisting stubbornly below 70 on account of, among other factors, chronic problems with drug and alcohol abuse. Russia has the highest HIV rate (along with Ukraine), the highest homicide rate and the highest prison population of the former Soviet Union. It languishes near the bottom of the Global Peace Index. Elections, once pluralistic and even commended by the OSCE, are once again foregone conclusions; governors, once elected, are now appointed. The 'vertical' of power centred on the Kremlin appears as strong as it was in Soviet times.

Download the data

DATA: download the full spreadsheet

More open data

Data journalism and data visualisations from the Guardian

World government data

Search the world's government data with our gateway

Development and aid data

Search the world's global development data with our gateway

Can you do something with this data?

Flickr Please post your visualisations and mash-ups on our Flickr group

Contact us at data@guardian.co.uk

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion